Congress is developing recovery legislation that would make historic investments to help reduce poverty and racial disparities, rebuild the country’s infrastructure, promote climate resiliency, create well-paying jobs, and more. Some of the investments in this package — based in large part on the American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan the Biden Administration introduced this year — would be much more effective if the low-income households they are designed to benefit are able to afford stable housing. While the Administration’s proposal included some $300 billion for housing, nearly all of it would subsidize construction and renovation, with less than 1 percent going toward the rental assistance needed to help millions of people with incomes around or below the poverty line afford housing. The package would do far more to expand opportunity and reduce hardship for people with the lowest incomes — and who need these resources most — if it also includes a major expansion of rental assistance through the Housing Choice Voucher program. Additional vouchers could strengthen investments in:

- Housing construction and rehabilitation, by making rents in new or rehabilitated units affordable for people with extremely low incomes;

- Preschool, quality child care, and K-12 education, by preventing housing instability that causes children to bounce from school to school, and homelessness and overcrowding that disrupt children’s sleep and schoolwork and harm their development in other ways;

- Home- and community-based services, by helping older adults and people with disabilities afford accessible homes in the community and avoid or leave institutional settings;

- Community college, by providing stable housing that allows students to focus on completing their degree or certificate program; and

- Broadband, by maintaining people’s housing security so they can more fully benefit from access to high-speed internet.

Millions of households with low incomes spend more than half of their income on housing, experience homelessness, or face other forms of housing insecurity. The Housing Choice Voucher program and other federal rental assistance, which are highly effective at reducing homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding, are critical components to addressing the issue.[1] Unfortunately, these programs only reach about 1 in 4 eligible families due to funding limitations. And for households that do ultimately receive a voucher, they must typically wait years for help.[2]

Housing affordability challenges are heavily concentrated among people with the lowest incomes and people of color, due in part to the country’s long history of racist policies. Of the 11.2 million renter households that paid more than half of their income for housing in 2018, close to three-fourths had extremely low incomes (up to the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the local median, whichever is higher) and more than 60 percent were people of color.[3] On a single night in January 2020, 580,000 people experienced homelessness, and nearly 4 out of 10 of those individuals were Black.[4] These households, which are most in need of housing assistance, could miss out on the benefits of other investments without rental assistance to provide a stable, accessible home and to avoid housing insecurity.

The Administration’s recovery proposals call for major capital investments in housing construction and rehabilitation. These investments would increase the supply of housing, particularly in rental markets with low vacancy rates. They would also improve energy efficiency, remove lead paint and other health hazards, and provide more housing that is accessible to people with disabilities. However, supply-side investments alone will leave out many people with the greatest housing needs. Expanding rental assistance through the Housing Choice Voucher program, which helps to cover the difference between high rent prices and low incomes,[5] would ensure that people with the lowest incomes can afford to rent the additional and improved housing provided through capital housing investments, as well as other modest homes they choose in the private market.

Many of the capital subsidies used to renovate or build housing generally do not result in housing with rents that are affordable to households with the lowest incomes. Investments to support building or preserving housing usually do not cover the regular costs of operating and maintaining rental properties, making rents higher than what families with the lowest incomes can afford to pay. Pairing these resources with an expansion of the Housing Choice Voucher program would help ensure housing development investments can reach households with the greatest housing needs.

While this combination of targeted subsidies to increase the number of affordable homes with vouchers or other rental assistance can alleviate housing hardship — especially in places with rental housing shortages — vouchers alone will be sufficient to assist many families in other cities with an adequate housing supply but unaffordable rents. For example, both Houston and Indianapolis have had vacancy rates of around 10 percent in recent years,[6] suggesting a sufficient supply of housing; but nearly 4 in 5 households with extremely low incomes in these metro areas pay more than half of their income on rent.[7] In such cities, rental assistance would allow these families to secure stable housing by helping lower rents to an affordable level. Capital investments could improve housing quality and create more supportive housing, which combines affordable housing with supportive services such as intensive case management, housing navigation, and physical and behavioral health services. But for communities with a sufficient supply of housing, relying on housing development will have a limited impact on decreasing housing instability for the lowest-income households and would be less effective than expanding housing vouchers.[8]

Rental assistance through housing vouchers also provides greater choice for families with low incomes. Vouchers allow households to rent any privately owned housing (at a reasonable price for the area), providing families with flexibility over where they can live. The element of choice is particularly important for promoting equity because historical and ongoing policies and practices at the federal, state, and local level have limited housing options for people of color, particularly Black families, leading to segregated neighborhoods. Focusing housing investments solely on creating new housing inherently limits neighborhood options for low-income people and may not reflect their preferences.

Still, ensuring affordable housing exists in all neighborhoods is critical, and the Housing Choice Voucher program allows communities to “project base” a certain percentage of its vouchers so that the assistance is tied to a specific home. Connecting assistance to a certain place can help to ensure affordable housing exists in otherwise inaccessible well-resourced neighborhoods. Doing so can also preserve the affordability of homes both in neighborhoods that have historically not received investments and where rents are rapidly rising and people are at risk of displacement. Unlike other types of project-based rental assistance or affordable housing construction subsidies, families in homes with project-based vouchers can continue to receive rental assistance when they leave, and the subsidy remains for that home.[9] This helps to preserve affordable housing options in different neighborhoods while still allowing families to move without sacrificing their assistance. Because vouchers can move with a household and maintain affordability in a specific place, they provide optimum choice for families with low incomes and help promote housing equity.

The President’s recovery proposals include several focused on improving resources for children and their families, including providing universal preschool for all three- and four-year-old children and increasing access to affordable, quality child care. These resources would have long-term positive impacts on children and families, but housing instability could undermine the benefits and make accessing those programs more difficult.

Abundant research makes clear the importance of early childhood education for children’s long-term well-being and educational success.[10] Increased investments would be particularly beneficial for children of color, especially for Black and Latino children, who are more likely to be from families with low incomes or who live in neighborhoods that receive limited resources. The President’s recovery agenda also proposes resources to help improve access and quality of child care for low- and moderate-income families. Child care costs can prevent parents and other caregivers — particularly women — from pursuing educational and employment opportunities, which often affects both immediate and long-term earnings.[11]

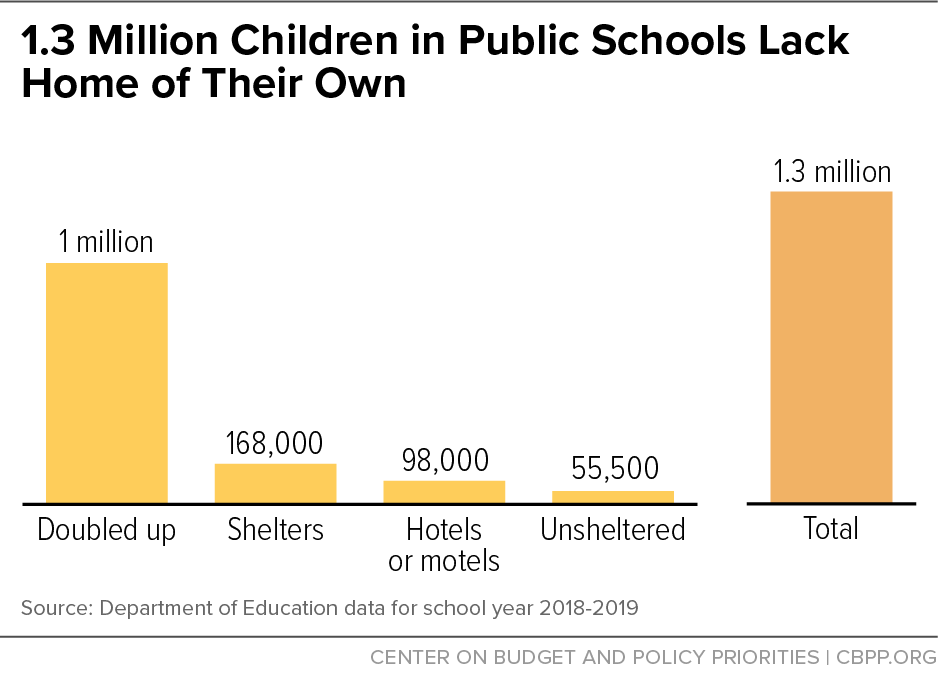

However, housing instability can undercut these efforts to promote children’s well-being and educational success. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 8 million children in low-income families faced housing affordability challenges,[12] and more than 1.3 million children experienced homelessness at some point during the 2018-2019 school year.[13] (See Figure 1.)

Homelessness, housing instability, and overcrowding negatively affect children’s health, development, and school performance. Evictions, doubling or tripling up with other families, and other forms of housing instability can force families to frequently move. Frequent moves are linked to attention and behavioral problems among preschool children, and homelessness is associated with physical and mental health issues, injuries, and poor school performance. Studies find that children living in crowded homes score lower on reading tests and complete less schooling than their peers.[14] Such housing insecurity also makes finding and maintaining work difficult for adults, even if they have reliable child care.

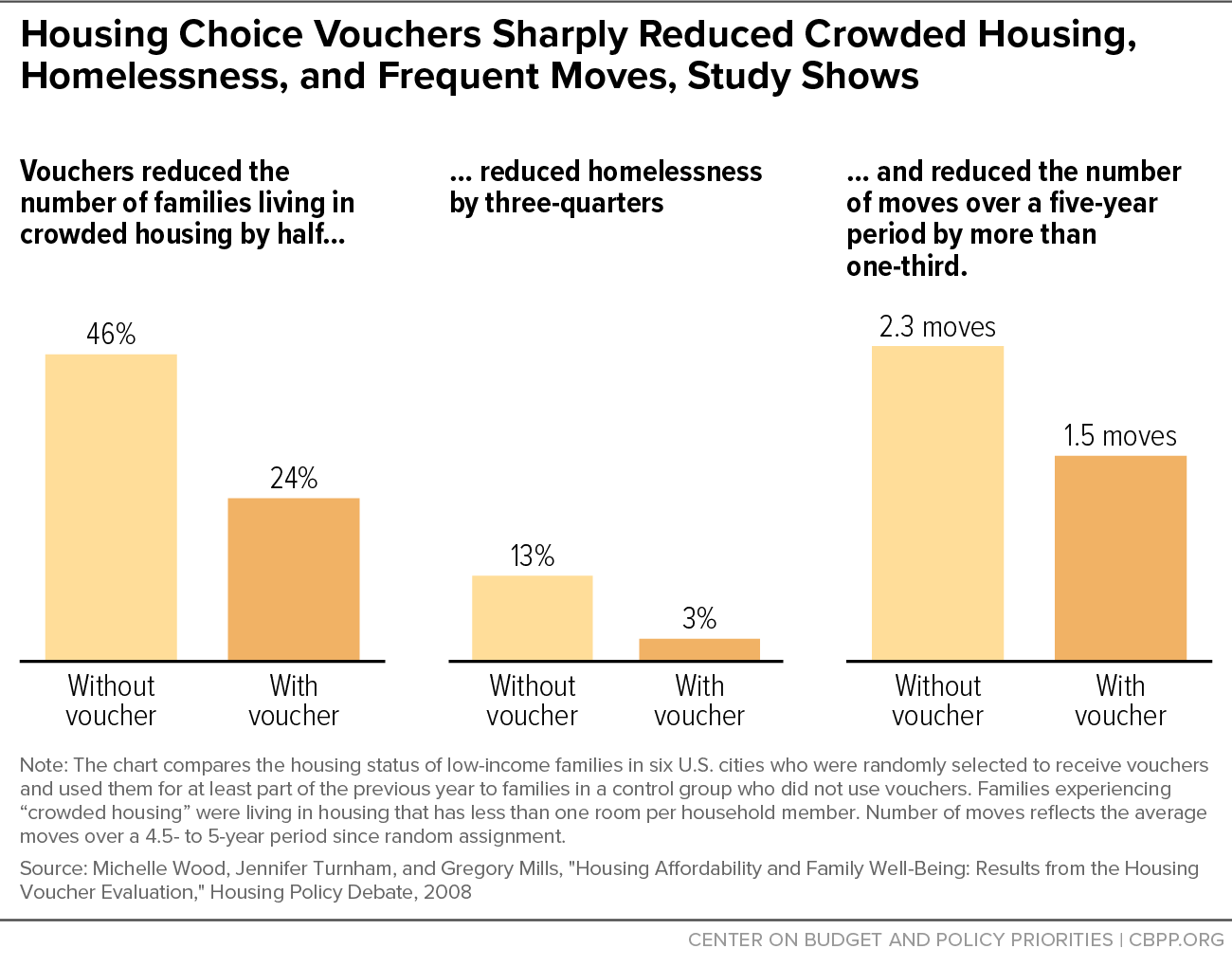

Rigorous research shows that the Housing Choice Voucher program reduces homelessness, housing instability, overcrowding, and poverty and has far-reaching implications for other aspects of children’s lives. (See Figure 2.) For example, vouchers help to improve test scores for some groups of children, and teenagers had higher earnings as adults (relative to a control group) for each additional year their family used a voucher or lived in public housing. Moreover, vouchers can reduce how frequently children change schools (or child care environments), making it easier for students to form bonds with peers and educators and for teachers to better gauge and advance their students’ learning.[15]

Reducing the frequency of school changes is particularly important for students with disabilities, who have individual education programs that would likely be reset at a new school. Further, vouchers provide additional choice for families to live near specific child care or schools that best suit their needs because the assistance moves with the family.

Ensuring children have safe, stable housing helps them succeed in school and would make additional investments in preschool, teacher readiness, and quality child care even more impactful for low-income children and families.

Expanding Housing Vouchers Would Complement an Expansion of Home- and Community-Based Services

Seniors and people with disabilities[16] overwhelmingly want to live in their own homes in the community instead of in institutions such as nursing homes,[17] but unaffordable rents and limited access to supportive services make that extremely difficult for people with low incomes. Medicaid is the main source of coverage for home- and community-based services (HCBS) — such as assistance with preparing meals, getting dressed, or attending appointments — which are typically not covered by private health insurance or Medicare. However, unlike nursing home care, state Medicaid programs are not required to cover HCBS.

Despite a significant shift in recent decades toward HCBS and away from institutionalized care as a share of Medicaid funding, access varies widely from state to state. Many people enrolled in Medicaid who could live in the community do not have access to HCBS and are forced to live in congregate care settings.[18] One 2011 estimate found that more than 1 million Medicaid enrollees living in institutional settings in 31 states may have been eligible for services to help them transition out of institutional care, but barriers such as lack of affordable housing and ineffective coordination between housing, health, and other service providers prevented people from making the transition.[19]

President Biden’s American Jobs Plan proposes to expand access to HCBS, strengthen the direct care workforce, and extend the Money Follows the Person (MFP) demonstration, which provides states with funds to help Medicaid beneficiaries move from an institution to a community-based setting. The Better Care Better Jobs Act, introduced in the Senate in June, carries forward the President’s bold recovery proposal by making MFP permanent and providing enhanced Medicaid funding for HCBS so states can increase access to services, ensure adequate payment rates, and strengthen data collection.[20] If included in recovery legislation, such an increase in federal resources for HCBS would help people move out of or avoid institutional care settings while increasing the number of professional caregivers and improving their training, working conditions, and wages.

While a critical investment, many of the lowest-income people would not benefit from the increase in HCBS unless they also receive rental assistance. Many older adults and people with disabilities, such as those who rely mainly or entirely on modest Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits, do not have enough income to afford rent in the private market. For example, over 2.2 million seniors and 4.4 million disabled adults under age 65 receive SSI, which has a basic monthly benefit of $794 for an individual in 2021. In many places, this amount isn’t enough to cover rent, even if people allocate every dollar to housing.[21] Even with an expansion in HCBS, many people would be forced to remain in or move to institutional settings or pay such high shares of their limited incomes on housing costs that they risk hardships such as eviction, homelessness, food insecurity, and utility shutoffs — all of which could jeopardize their health.[22]

In fact, state officials and researchers commonly cite lack of rental assistance as a key barrier to Medicaid enrollees eligible for MFP making the transition out of institutional care settings. Seventy-five percent of people who expressed interest in MFP could not participate because of unaffordable rent prices, Colorado officials reported in 2015.[23]

The Administration’s proposal to extend MFP beyond its current end date of 2023 would help assure participating states of continued funding. But an expansion of the housing voucher program would help address the lack of affordable, accessible housing and ensure more low-income people with disabilities and older adults can participate in the program.

Because vouchers can enable households to rent a home on the private market and communities to tie rental assistance to a specific place, they can help provide a flexible tool for serving older adults and disabled people. Some households can use vouchers to move out of institutions to a neighborhood that fits their needs, and others may need rental assistance to make their current home more affordable to avoid having to move from an existing community. A community can also use project-based vouchers to help ensure accessible homes remain affordable or be combined with coordinated services to create supportive housing.

Higher education is out of reach for many people due to cost, and as a result, so are jobs that require degrees or certificates beyond a high school diploma. To help more students, particularly those from low-income families, access higher education, the President’s recovery agenda includes proposals to reduce the costs of college. This includes making two years of community college free to all, increasing federal educational grants, investing in programs to improve college retention and completion, and expanding resources for Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Tribal Colleges and Universities, and other Minority-Serving Institutions. All of these proposals will help reduce barriers to higher education for students with low incomes, students of color, and those facing obstacles.

Focusing solely on access is not sufficient. President Biden has proposed investing $62 billion in programs to improve college retention and completion, which could provide necessary services to help students finish their degrees. Students face many hurdles to completing a program, including housing instability. For many low-income students, it is difficult to attend classes and engage with coursework if they are couch surfing, working multiple jobs to cover rent and other basic needs, or experiencing some form of housing instability. People with children or other caregiving responsibilities in particular may find it difficult to complete a program if they must prioritize providing for their dependents over their educational goals. About 15 percent of those attending community college are single parents, and 62 percent of all full-time community college students work at least part time.[24] In some situations, students can use financial aid to help pay for housing, but rising tuition and rent costs mean that even with the Administration’s proposed increases in federal, need-based aid, students would likely still face financial barriers.[25]

While the Housing Choice Voucher program does have some restrictions on students receiving assistance,[26] an expansion of the program would still help many housing-insecure students, including those from low-income families, with a disability or child, who are older than age 24, or exiting foster care. Seventeen percent of community college students said they experienced homelessness in the previous year, and 46 percent said they were housing insecure in a 2019 survey.[27] While the President’s proposal could provide needed services to students, it will not address students’ housing insecurity beyond one-time emergency payments. Rental assistance would provide these students with the stability they need to complete their programs and reach their goals.

As the pandemic has made clear, reliable internet access helps people more fully participate in society and the economy and is often necessary for people’s jobs, education, and health. President Biden’s recovery and infrastructure proposals recognize the importance of internet access by investing $100 billion to help provide affordable, reliable broadband across the country.

While this investment would help many more people access broadband, people with low incomes facing housing hardship may still encounter barriers. Housing instability could disrupt internet access if families must move or can’t afford both rent and internet costs, and those experiencing homelessness may not be able to charge or access a device to get online when internet is available. Even with internet access, overcrowded situations could leave children without a quiet place to focus on schoolwork, and adults without a space suitable for remote work or online medical appointments.

For the 11.2 million renter households paying more than 50 percent of their incomes on rents and utilities, even a minimal cost for broadband could be out of reach, as families make choices about how to use their limited budget and remain stably housed. While improved broadband could help many people experiencing homelessness or housing instability find information on housing resources, they will still not be able to get any help without additional funding for rental assistance. Expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program would also free up more of people’s incomes to afford reasonably priced broadband and help maintain their housing security so they can more fully enjoy the benefits of high-speed internet access.