State Medicaid Agencies Can Partner With WIC Agencies to Improve the Health of Pregnant and Postpartum People, Infants, and Young Children

End Notes

[1] This report was prepared with support from Sonya Schwartz, an independent consultant. It draws heavily on an earlier paper written by Donna Cohen Ross, an independent consultant, for the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[2] Writing about pregnancy has often assumed cisgender identities, with the use of terms like “pregnant women.” Such language excludes people who are transgender or non-binary who give birth. In this report we attempt to be more inclusive by referring to pregnant people or using other non-gendered language wherever possible, while in places using gendered labels to avoid misrepresenting the data or quality measures we are citing.

[3] Other eligibility requirements are described in the text box “WIC Basics.”

[4] Jennifer M. Haley et al., “Uninsurance Rose Among Children and Parents in 2019,” Urban Institute, July 2021, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104547/uninsurance-rose-among-children-and-parents-in-2019.pdf.

[5] Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, “National and State Estimates of WIC Eligibility and Program Reach in 2021,” November 2023, Table 5.1, https://www.fns.usda.gov/research/wic/eligibility-and-program-reach-estimates-2021.

[6] Elizabeth Hinton, “A Look at Recent Medicaid Guidance to Address Social Determinants of Health and Health-Related Social Needs,” KFF, February 22, 2023, https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/a-look-at-recent-medicaid-guidance-to-address-social-determinants-of-health-and-health-related-social-needs/.

[7] This piece uses the term “pregnancy-related deaths” even if the underlying study used the term “maternal deaths.”

[8] The White House, “White House Blueprint For Addressing The Maternal Health Crisis,” June 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Maternal-Health-Blueprint.pdf.

[9] The maternal mortality rate is three times higher for Black women than for white women. See the Commonwealth Fund, “The U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis Continues to Worsen: An International Comparison,” December 1, 2022, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/us-maternal-mortality-crisis-continues-worsen-international-comparison.

[10] Danielle M. Ely and Anne K. Driscoll, “Infant Mortality in the United States: Provisional Data From the 2022 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death File,” National Center for Health Statistics, November 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr033.pdf.

[11] AIAN and Hispanic people have had a higher risk for COVID-19 infection, and AIAN, Hispanic, and Black people have had a higher risk for hospitalization and death due to COVID-19. These are cumulative and age-adjusted data from April 2020 to October 2022. Latoya Hill, Samantha Artiga, and Mambi Ndugga, “COVID-19 Cases, Deaths and Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity as of Winter 2022,” KFF, March 7, 2023, Figure 1, https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-cases-deaths-and-vaccinations-by-race-ethnicity-as-of-winter-2022/.

[12] Lauren Hall, “Food Insecurity Increased in 2022, With Severe Impact on Households With Children and Ongoing Racial Inequities,” CBPP, October 26, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/food-insecurity-increased-in-2022-with-severe-impact-on-households-with-children-and-ongoing.

[13] In addition, the National Governor’s Association issued a playbook on “Tackling the Maternal and Infant Health Crisis.” See National Governors Association, “Maternal and Infant Health,” https://www.nga.org/maternal-infant-health/.

[14] Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, “National and State Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and Program Reach in 2020,” updated January 9, 2023, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/eligibility-and-program-reach-estimates-2020.

[15] Steven Carlson and Zoë Neuberger, “WIC Works: Addressing the Nutrition and Health Needs of Low-Income Families for More Than Four Decades,” CBPP, updated January 27, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wic-works-addressing-the-nutrition-and-health-needs-of-low-income-families

[16] Steven Carlson and Joseph Llobrera, “SNAP Is Linked With Improved Health Outcomes and Lower Health Care Costs,” CBPP, December 14, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-is-linked-with-improved-health-outcomes-and-lower-health-care-costs.

[17] Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services, “Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment,” https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/early-and-periodic-screening-diagnostic-and-treatment/index.html.

[18] The Social Security Act at 1902(a)(11)(C) and 1902(a)(53) requires Medicaid to notify all pregnant or breastfeeding people and young children of the availability of the benefits of WIC and to coordinate vaccinations with WIC. Medicaid regulations at 42 C.F.R. § 431.635 implement these requirements. In addition, the regulation specifies that Medicaid must effectively inform individuals who are blind or deaf or who cannot read or understand the English language.

[19] Michelle J.K. Osterman et al. “Births: Final Data for 2021,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, January 31, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr72/nvsr72-01.pdf.

[20] The four states are Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. See KFF, “Births Financed by Medicaid,” 2021, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/births-financed-by-medicaid/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Percent%20of%20Births%20Financed%20by%20Medicaid%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D.

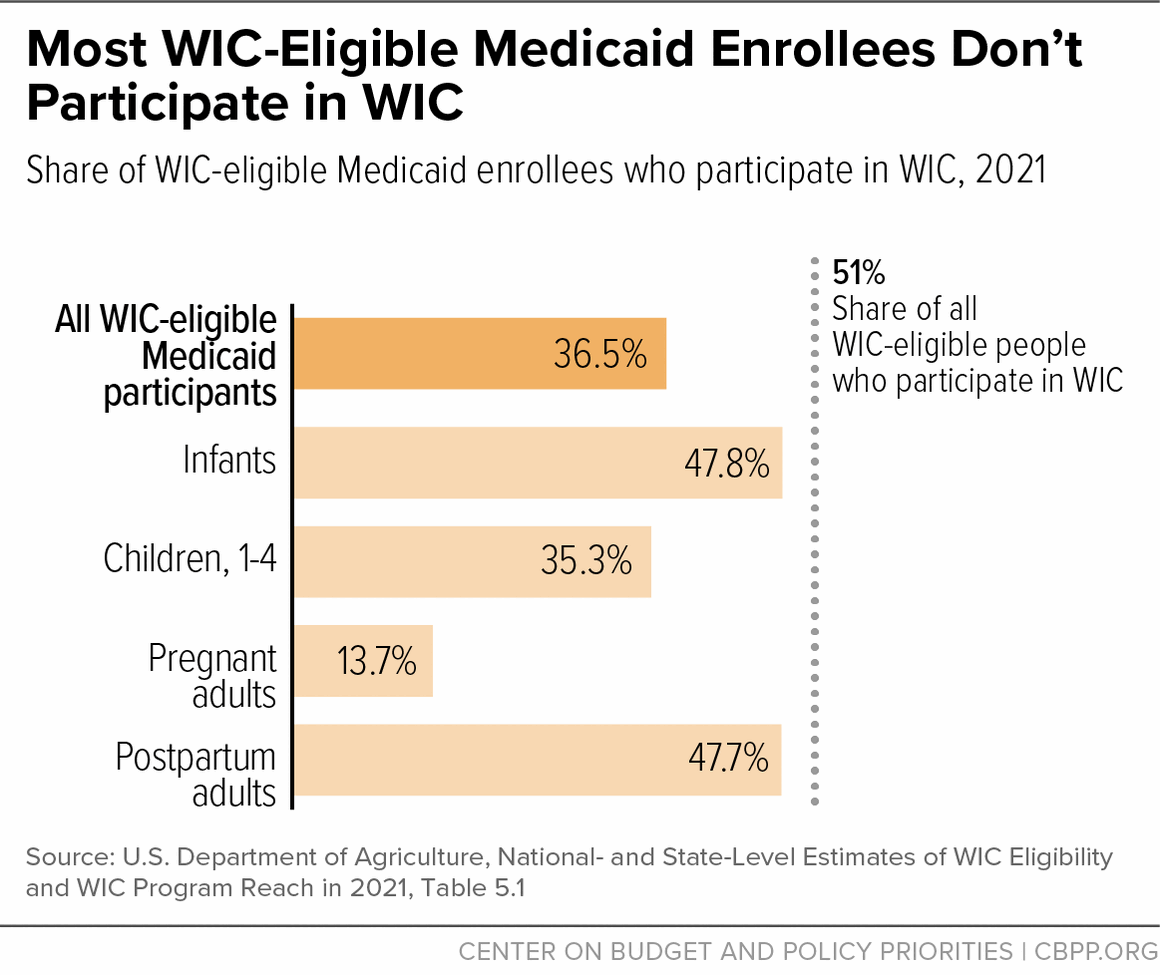

[21] Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, “National and State Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and Program Reach in 2021,” November 2023, https://www.fns.usda.gov/research/wic/eligibility-and-program-reach-estimates-2021.

[22] Ibid., Table 5.1.

[23] Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022, H.R. 2471, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2471/text.

[24] KFF, “Medicaid Postpartum Coverage Extension Tracker,” September 21, 2023, https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-postpartum-coverage-extension-tracker/.

[25] By law, infants born to Medicaid enrollees are automatically covered until the child turns 1, but this option can help ensure that postpartum people also receive health care services in this important time period.

[26] Currently, 23 states provide continuous eligibility to children in Medicaid. The CAA requirement will bring the remaining 27 states and the District of Columbia in line. See KFF, “State Adoption of 12-Month Continuous Eligibility for Children’s Medicaid and CHIP,” January 1, 2023, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-adoption-of-12-month-continuous-eligibility-for-childrens-medicaid-and-chip.

[27] Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, “WIC Policy Memorandum #2023-5: Data Sharing to Improve Outreach and Streamline Certification in WIC,” April 25, 2023, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/data-sharing.

[28] USDA is entering into a cooperative agreement with the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Benefits Data Trust, and the National WIC Association to oversee the grant process, provide technical assistance, and help evaluate state efforts. See Food and Nutrition Service, “FNS awards cooperative agreement to streamline enrollment in WIC through data matching,” https://www.fns.usda.gov/news-item/fns-016.23, and “FY 2023 WIC Enrollment via State-Level Referral Data Matching with SNAP and Medicaid,” 2023, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/data-sharing-rfa.

[29] CMS, CMCS Informational Bulletin, “Coverage of Services and Supports to Address Health-Related Social Needs in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program,” November 16, 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-11/cib11162023.pdf; CMS, “Coverage of Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) Services in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP): November 2023,” https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-11/hrsn-coverage-table.pdf; CMS, “Addressing Health-Related Social Needs in Section 1115 Demonstrations,” December 6, 2022, https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-01/addrss-hlth-soc-needs-1115-demo-all-st-call-12062022.pdf; Anne Marie Costello, Letter to State Health Officials, SHO# 21-001 RE: Opportunities in Medicaid and CHIP to Address Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), January 7, 2021, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho21001.pdf.

[30] An in-depth discussion of state options to address HRSNs through Medicaid is forthcoming from CBPP’s Allison Orris, Anna Bailey, and Jennifer Sullivan, titled “States Have Flexibility to Use Medicaid to Address Health-Related Social Needs.”

[31] Danielle Daly, Letter to Dawn Stehle, Arkansas Department of Human Services, December 28, 2022, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/ar-arhome-demo-appvl-12282022.pdf; Daniel Tsai, Letter to Carmen Heredia, Arizona Healthcare Cost Containment System, June 7, 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/az-coid-chip-demonstn-aprl-ca.pdf; Angela Garner, Letter to Mike Levine, Executive Office of Health and Human Services, June 21, 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/ma-masshealth-apprvl-06212023.pdf, Chiquita Brooks La-Sure, Letter to Jennifer Jacobs, Division of Medical Assistance and Health Services, March 30 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/downloads/nj-1115-cms-exten-demnstr-aprvl-03302023.pdf; Daniel Tsai, Letter to Charissa Fotinos, Washington Health Care Authority, June 30, 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-06/wa-medicaid-transformation-ca-06302023.pdf; Daniel Tsai, Letter to Dana Hittle, Oregon Health Authority, April 20, 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-04/or-health-plan-ca-04202023.pdf.

[32] The White House, “White House Blueprint For Addressing The Maternal Health Crisis,” June 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Maternal-Health-Blueprint.pdf.

[33] The White House, June 2022, see section 5.1, pp. 51-52.

[34] The White House, June 2022, see section 3.1, p. 38.

[35] The White House, “Biden-Harris Administration National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health,” September 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/White-House-National-Strategy-on-Hunger-Nutrition-and-Health-FINAL.pdf

[36] The White House, September 2022, p. 16.

[37] The White House, September 2022, p. 19.

[38] The White House, “U.S. Playbook to Address Social Determinants of Health,” November 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/SDOH-Playbook-3.pdf; HHS, “Call to Action: Addressing Health-Related Social Needs in Communities Across the Nation,” November 2023, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/3e2f6140d0087435cc6832bf8cf32618/hhs-call-to-action-health-related-social-needs.pdf.

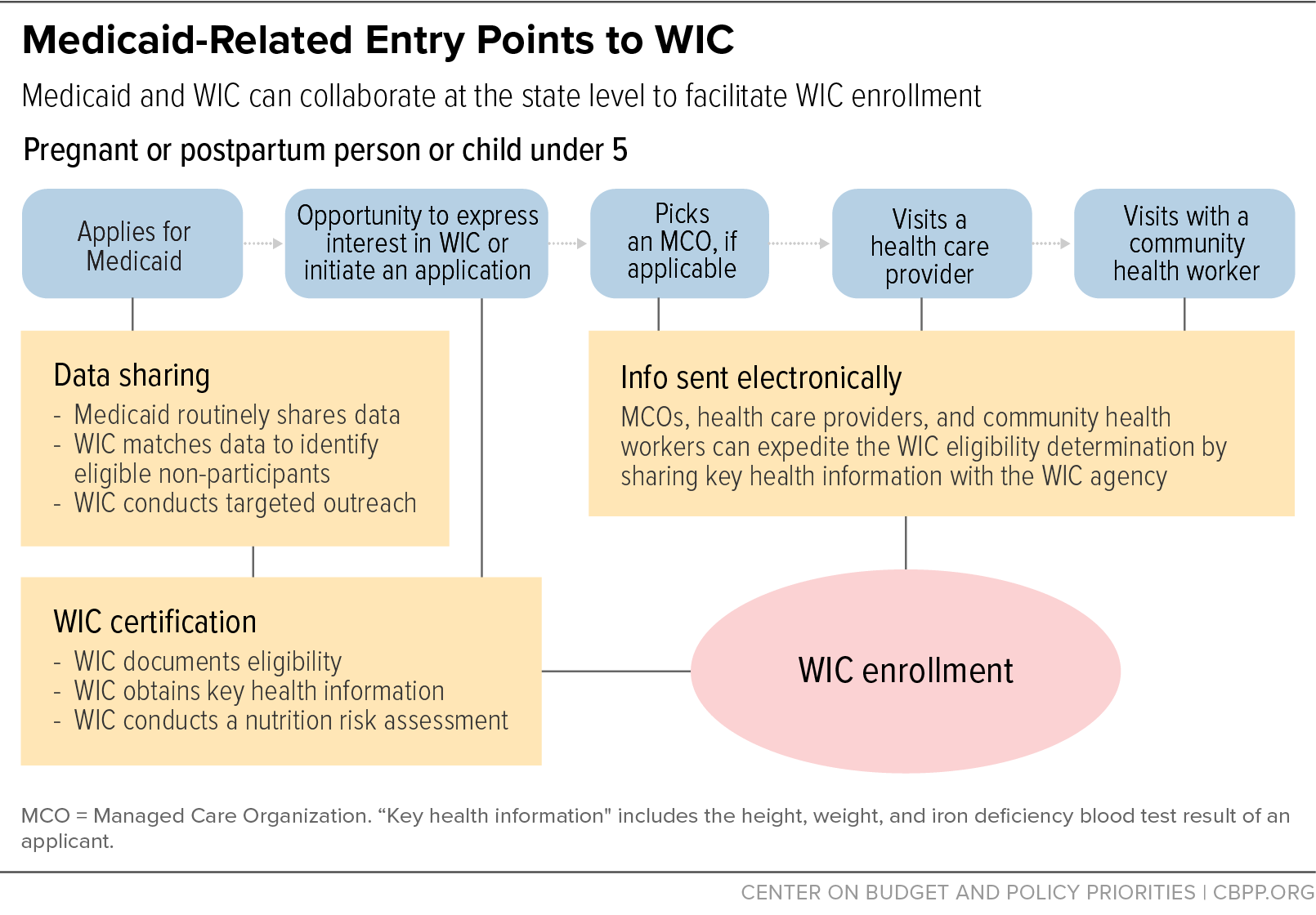

[39] The majority of Medicaid enrollees — 72 percent of all enrollees and 85 percent of children — receive their Medicaid coverage through a Medicaid managed care organization. Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), “Exhibit 30. Percentage of Medicaid Enrollees in Managed Care by State and Eligibility Group,” December 2023, https://www.macpac.gov/publication/percentage-of-medicaid-enrollees-in-managed-care-by-state-and-eligibility-group/.

[40] Recipients of SNAP and monthly TANF cash assistance payments are also adjunctively eligible for WIC. For more details about the adjunctive eligibility rules, see 7. C.F.R. § 246.7 (d)(2)(vi), https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/7/246.7.

[41] States with such automated systems do not necessarily have a written agreement in place and do not need to receive batches of data to check applicants’ adjunctive eligibility. For more information about each state’s practices for checking for adjunctive eligibility, see Zoë Neuberger and Lauren Hall, “State WIC Agencies Continue to Use Federal Flexibility to Streamline Enrollment,” CBPP, updated November 14, 2022, Table 1, www.cbpp.org/wiccertificationpolicies.

[42] Long-standing federal rules require applicants to be present during certification appointments, with exceptions for newborn infants, children with working parents, and individuals with health conditions that prevent them from attending in-person appointments. (See 7 C.F.R. § 246.7(o).) Under federal waivers provided during the pandemic, WIC agencies switched to conducting appointments by telephone or videoconference, and did not have to collect anthropometric information. Under American Rescue Plan authority, these waivers have been extended through September 2026, but WIC agencies must now collect anthropometric information. See Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Flexibilities to Support Outreach, Innovation, and Modernization,” August 4, 2023, https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/modernization/flexibilities. Receiving that information from health care providers eliminates the need for an appointment at a WIC clinic.

[43] For state-by-state information, see Zoë Neuberger and Lauren Hall, “WIC Coordination With Medicaid and SNAP,” updated November 14, 2022, www.cbpp.org/wiccollaborationsurvey.

[44] U.S. Department of Agriculture, “National- and State-Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and WIC Program Reach in 2021,” Table 5.1, https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/wic-eligibility-report-vol1-2021.pdf.

[45] See Jess Maneely and Zoë Neuberger, “Using Data Matching and Targeted Outreach to Enroll Families With Young Children in WIC,” CBPP and Benefits Data Trust, January 5, 2021, Figure 1, www.cbpp.org/wicpilotreport.

[46] National WIC Association, “New Mexico WIC and SNAP Integration,” December 16, 2022, https://thewichub.org/new-mexico-wic-and-snap-integration/.

[47] For more information about how to incorporate WIC into an online application, see CBPP, “Assessing Your WIC Certification Practices,” https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/assessing-your-wic-certification-practices#question-enrollment-3.

[48] For example, Kansas’s Medicaid agency used SNAP data to conduct WIC outreach in communities with significant Black, Latino, and Native American populations who face disparate levels of food insecurity. American Public Human Services Association, “Kansas Spotlight: Forming Connections Between SNAP and WIC to Tackle Food Insecurity,” https://files.constantcontact.com/391325ca001/90c636ac-96e1-4cc5-8e2b-f62af781fdda.pdf.

[49] For more information see National WIC Association, “Minnesota WIC Data Matching and Targeted Outreach,” November 21, 2022, https://thewichub.org/minnesota-wic-data-matching-and-targeted-outreach/.

[50] For results of pilots conducted in Colorado, Massachusetts, Montana, and Virginia, see Jess Maneely and Zoë Neuberger, “Targeted Text Message Outreach Can Increase WIC Enrollment, Pilots Show,” Benefits Data Trust and CBPP, June 10, 2021, www.cbpp.org/wictexting.

[51] For planning tools and resources on how to launch data matching and targeted outreach, see CBPP and Benefits Data Trust, “Toolkit: Increasing WIC Coverage Through Cross-Program Data Matching and Targeted Outreach,” March 1, 2022, www.cbpp.org/wiccrossenrollmenttoolkit. For information on which states are conducting targeted outreach, see Zoë Neuberger and Lauren Hall, “ WIC Coordination With Medicaid and SNAP,” updated November 14, 2022, Table 1, www.cbpp.org/wiccollaborationsurvey. For information on federal funding see Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, “FNS awards cooperative agreement to streamline enrollment in WIC through data matching,” September 21, 2023, https://www.fns.usda.gov/news-item/fns-016.23#:~:text=The%20Bloomberg%20School%20and%20its%20collaborators%2C%20Benefits%20Data%20Trust%20and,of%20other%20federal%20programs%20like. For more information on when federal funding is likely to be available, see Food and Nutrition Service, USDA, “FY 2023 WIC Enrollment via State-Level Referral Data Matching with SNAP and Medicaid,” 2023, p. 16, available at https://www.grants.gov/search-results-detail/347786.

[52] For example, Colorado has developed an online WIC referral form that is promoted to health care providers so they can refer patients directly to WIC. Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, “Colorado WIC Families- Referral Form,” https://www.healthinformatics.dphe.state.co.us/WICSignUp.

[53] For example, New Jersey’s WIC program has developed a referral form for providers that allows them to share the anthropometric information needed for WIC nutrition risk assessments. New Jersey WIC, “New Jersey WIC Health Care Referral,” https://www.state.nj.us/health/forms/wic-41.pdf.

[54] For more suggestions on how WIC and health care providers can coordinate services, see CBPP, “Assessing Your WIC Certification Practices,” https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/assessing-your-wic-certification-practices#questions-coordinating.

[55] See Santa Cruz County’s Serving Communities Health Information Organization project, California WIC Association, “Santa Cruz Multi-Partner Linkage Supports WIC Referrals and Enrollment,” https://www.calwic.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Community-Bridges-and-SCHIO-Summary.pdf, and San Francisco Department of Public Health’s electronic health records project, “San Francisco WIC Linkage with Epic Electronic Health Record System,” https://www.calwic.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/San-Francisco-Summary.pdf. In these projects the WIC agency indicates when a referral has been received but not whether the individual has been enrolled in WIC.

[56] Carmen L. Green et al., “The Cycle to Respectful Care: A Qualitative Approach to the Creation of an Actionable Framework to Address Maternal Outcome Disparities,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, May 6, 2021, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8141109/.

[57] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Exhibit 30. Percentage of Medicaid Enrollees in Managed Care by State and Eligibility Group,” December 2023, https://www.macpac.gov/publication/percentage-of-medicaid-enrollees-in-managed-care-by-state-and-eligibility-group/.

[58] North Carolina of Health and Human Services, “Healthy Opportunities,” https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities and “NCCARE360,” https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/department-initiatives/healthy-opportunities/nccare360.

[59] Washington Health Care Authority, “Community Health Worker (CHW) Grant,” https://www.hca.wa.gov/about-hca/programs-and-initiatives/clinical-collaboration-and-initiatives/community-health-worker-chw-grant.

[60] Preventive Services Initiatives, defined in federal regulation (42 CFR 440.130(c)) and law (Social Security Act 1905(a)(13), and Cindy Mann, “Update on Preventive Services Initiatives,” CMS Center for Medicaid & CHIP Services, November 27, 2013, https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/CIB-11-27-2013-Prevention.pdf. .

[61] Tomás Guarnizo, “Doula Services in Medicaid: State Progress in 2022,” Center for Children and Families, Georgetown University, June 2, 2022, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2022/06/02/doula-services-in-medicaid-state-progress-in-2022/.

[62] Ruth A. Hughes, Letter to Tricia Roddy, Maryland Department of Health, June 15, 2022, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/spa/downloads/MD-22-0005.pdf.

[63] New Jersey recently reported low use of doula services, which began in 2021, and attributed it to lack of awareness among Medicaid enrollees about the doula benefit and workforce issues. MACPAC, “Doulas in Medicaid: Case Study Findings,” November 2023, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Doulas-in-Medicaid-Case-Study-Findings.pdf. To help address these concerns, the N.J. Department of Health convened the New Jersey Doula Learning Collaborative in 2022, which, through the support of HealthConnect One, is providing training, workforce development, supervision support, mentoring, technical assistance, direct billing, and sustainability planning for community doulas and doula organizations throughout the state. Also in 2022, CMS approved N.J.’s amended State Medicaid Plan to increase the reimbursement rate for maternity service clinicians and community doulas. National Health Law Program, “Current State Doula Medicaid Efforts,” https://healthlaw.org/doulamedicaidproject/.

[64] New Jersey Department of Human Services, Division of Medical Assistance & Health Services, “Medicaid/NJ FamilyCare Coverage of Doula Services Revised Billing Codes,” February 2021, https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/dmahs/info/Newsletter_31-04_Doula.pdf.

[65] Oregon SPA #17-0006, CMS Approval letter and Approved SPA. David L. Meacham, Letter to Lynne Saxton, Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Medicaid and Children’s Health Operations, July 19, 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/State-resource-center/Medicaid-State-Plan-Amendments/Downloads/OR/OR-17-0006.pdf.

[66] Carl Rush, Elinor Higgins, and Sandra Wilkniss, “State Approaches to Community Health Worker Financing through Medicaid State Plan Amendments,” National Academy for State Health Policy, December 7, 2022, https://nashp.org/state-approaches-to-community-health-worker-financing-through-medicaid-state-plan-amendments/.

[67] Ibid.

[68] Social Security Act § 2105(a)(1)(D)(ii). State spending on HSIs counts toward the overall 10 percent cap on spending for administrative expenses, which also includes the cost of administering the program, outreach, and other activities. As of July 2019, 24 states had one or more approved HSIs. See Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “CHIP Health Services Initiatives: What They Are and How States Use Them,” July 2019, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/CHIP-Health-Services-Initiatives.pdf. For a description of services and supports considered allowable under CHIP HSIs, see CMS, “Coverage of Health-Related Social Needs Services in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program,” November 2023, https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-11/hrsn-coverage-table.pdf.

[69] Anita Cardwell, “Leveraging CHIP to Improve Children’s Health: An Overview of State Health Services Initiatives,” National Academy for State Health Policy, May 20, 2019, https://nashp.org/leveraging-chip-to-improve-childrens-health-an-overview-of-state-health-services-initiatives/.

[70] Federal Match Rates for Medicaid Administrative Activities, 42 CFR 432.50; 42 CFR 435.15. See Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Federal Match Rates for Medicaid Administrative Activities,” https://www.macpac.gov/federal-match-rates-for-medicaid-administrative-activities/. Most administrative expenditures are matched at 50 percent, but certain activities are eligible for a higher matching rate, such as investments in translation services (matched at 75 percent) and health information technology (matched at 90 percent).

[71] Costello, op. cit.

[72] Veronnica Thompson and Anoosha Hasan, “Medicaid Reimbursement for Home Visiting Services,” National Academy for State Health Policy, May 1, 2023, https://nashp.org/medicaid-reimbursement-for-home-visiting-services/.

[73] Michigan leaders also used contract incentives to expand access to community-based providers. Medicaid MCO plans in Michigan are required to contract with at least one community health worker for every 5,000 members. See Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, “State of Michigan Contract No. Comprehensive Health Care Program for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services,” 2021, https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/-/media/Project/Websites/mdhhs/Folder1/Folder101/contract_7696_7.pdf .

[74] State of Illinois, “Model Contract,” January 24, 2018, https://interactives.commonwealthfund.org/medicaidmcdb/contracts/IL1_201824001MCOModelContractRev3RedLine.pdf?_gl=1*tqf6dn*_gcl_au*MTU0ODUxNzU5OC4xNjg3NTM4MjM4.

[75] Florida Medicaid Managed Care Contract; see the Agency of Health Care Administration, “Attachment II Exhibit II-A – Update: February 1, 2022 Managed Medical Assistance (MMA) Program,” p. 40, https://ahca.myflorida.com/content/download/9938/file/Exhibit_II_A_MMA-2022-02-01.pdf.

[76] MassHealtb, Accountable Care Partnership Plan Contracts, https://www.mass.gov/lists/accountable-care-partnership-plan-contracts.

[77] Oregon Health Authority, “Health-Related Services Guide for CCOs: Traditional Health Workers and Health-Related Services,” updated November 2022, https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/dsi-tc/Documents/Health-Related-Services-Guide-THWs.pdf.

[78] Oregon Health Authority, “Oregon Medicaid Fee-for-Service reimbursement for Community Health Workers,” updated September 1, 2020, https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HSD/OHP/Tools/CHW_Billing%20Guide.pdf.

[79] Oregon Health Authority, 2022, op. cit.

[80] Ibid.

[81] Tricia Brooks, “Measuring and Improving Health Care Quality for Children in Medicaid and CHIP: A Primer for Child Health Stakeholders,” Georgetown University Health Policy Institute Center for Children and Families, March 2016, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Measuring_Health_Quality_Medicaid_CHIP_Primer.pdf.

[82] Ibid.

[83] Medicaid.gov, “2023 Core Set of Adult Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid (Adult Core Set),” https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-08/2023-adult-core-set_0.pdf.

[84] Medicaid.gov, “2023 Core Set of Children’s Health Care Quality Measures for Medicaid and CHIP (Child Core Set),” https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-08/2023-child-core-set_0.pdf.

[85] Medicaid.gov, “2023 Core Set of Maternal and Perinatal Health Measures for Medicaid and CHIP (Maternity Core Set),” https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2023-08/2023-maternity-core-set.pdf.

[86] Kathryn R. Fingar et al., “Reassessing the Association between WIC and Birth Outcomes Using a Fetuses-at-Risk Approach,” Maternal Child Health Journal, Vol. 21, No. 4, April 2017, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27531011/. For a discussion of additional research on the relationship between WIC participation and birthweight, see Steven Carlson and Zoë Neuberger, “WIC Works: Addressing the Nutrition and Health Needs of Low-Income Families for More Than Four Decades,” CBPP, updated January 27, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/5-4-15fa.pdf.

[87] Recent USDA-sponsored research following mothers and children who enrolled in WIC as infants shows that nearly all (95 percent) have a doctor’s office, health clinic, or other medical facility that they visit for routine physical examinations and wellness checks by the time their child nears his or her 4th birthday. Tracy Thomas et al., “Assessing Immunization Interventions in the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 47, No. 5, November 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.017.

[88] Tim Bersak and Lyudmyla Sonchak, “The impact of WIC on infant immunizations and healthcare utilization,” Health Services Research, Vol. 53, S1, August 2018, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12810; Thomas et al., op. cit.

[89] Federal Register “Medicaid Program and CHIP; Mandatory Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Core Set Reporting,” August 31, 2023, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/08/31/2023-18669/medicaid-program-and-chip-mandatory-medicaid-and-childrens-health-insurance-program-chip-core-set.

[90] EPSDT also requires coverage of medically necessary “interperiodic” screening outside of the state’s periodicity schedule. Coverage for such screenings is required based on an indication of a medical need to diagnose an illness or condition that was not present at the regularly scheduled screening or to determine if there has been a change in a previously diagnosed illness or condition that requires additional services. The determination of whether an interperiodic screen is medically necessary may be made by a health, developmental, or educational professional who comes into contact with the child outside of the formal health care system (e.g., state early intervention or special education programs, Head Start and day care programs, WIC, and other nutritional assistance programs). This includes, for example, personnel working for state early intervention or special education programs, Head Start, and WIC. A state may not limit the number of medically necessary screenings a child receives and may not require prior authorization for either periodic or interperiodic screenings. See Department of Health and Human Services, “EPSDT - A Guide for States: Coverage in the Medicaid Benefit for Children and Adolescents,” June 2014, https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/2019-12/epsdt_coverage_guide.pdf.

[91] There are different ways that states can provide rewards or payments to plans that are beyond the scope of this paper. Shilpa Patel and Laurie C. Zephyrin, “Medicaid Managed Care Opportunities to Promote Health Equity in Primary Care,” Commonwealth Fund, December 19, 2022, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2022/medicaid-managed-care-opportunities-promote-health-equity-primary-care.

[92] Oregon Health Authority, “CCO Incentive Metrics & WIC,” https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/HEALTHYPEOPLEFAMILIES/WIC/Documents/cco-metrics-wic.pdf.

[93] Oregon’s Coordinated Care Organizations are built on the foundation of Oregon’s MCOs, but have multiple features that distinguish them from MCOs: CCOs are locally governed, with representation from Medicaid members, health care providers, and other local stakeholders.

[94] Oregon Health Authority, “2023 CCO Quality Incentive Program: Measure Summaries,” January 2023, https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/CCOMetrics/PlainLanguageIncentiveMeasures.pdf.

[95] Oregon Health Authority, “SDOH Screening & Referral Metric: Frequently Asked Questions,” updated September 2023, https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/dsi-tc/Documents/SDOH-Screening-Metric-FAQ.pdf.

[96] State of Pennsylvania, Department of Human Services, “2023 Community HealthChoices Agreement,” January 2023, https://www.dhs.pa.gov/HealthChoices/HC-Services/Documents/2023%20HealthChoices%20Agreement%20including%20Exhibits%20and%20Non-financial%20Appendices.pdf.

[97] CMS, “CMS Strategic Plan,” September 27, 2023, https://www.cms.gov/cms-strategic-plan.

[98] Anne Marie Costello, Letter to State Health Officials, January 7, 2021https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho21001.pdf.

[99] CMS, “Health Related Social Needs,” https://www.medicaid.gov/health-related-social-needs/index.html.

[100] Daniel Tsai, Letter to State Medicaid Directors, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, January 4, 2023. “https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd23001.pdfIn lieu of” services can be used at the option of the managed care plan and the enrollee as long as they are a cost-effective substitute for state plan services and settings.

[101] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Managed Care Access, Finance, and Quality Proposed Rule, 88 Fed. Reg. 28092, May 3, 2023, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2023-05-03/pdf/2023-08961.pdf.

[102] Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, HHS, “White House Challenge to End Hunger and Build Healthy Communities,” https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/white-house-conference-hunger-nutrition-and-health/make-commitment#:~:text=Invest%20in%20health%2Drelated%20social,about%20nutrition%20and%20physical%20activity

[103] No Kid Hungry, “Share Our Strength Announces Commitments in Support of the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition and Health,” September 28, 2022, www.nokidhungry.org/who-we-are/pressroom/share-our-strength-announces-commitments-support-white-house-conference-hunger#:~:text=By%202030%2C%20the%20American%20Academy,federal%20and%20community%20nutrition%20resources.

[104] No Kid Hungry, “No Kid Hungry providing 14 state AAP chapters with $280,000 in grants to fuel strategy,” December 13, 2022, https://www.nokidhungry.org/who-we-are/pressroom/release-no-kid-hungry-and-american-academy-pediatrics-expand-partnership.

[105] American Academy of Pediatrics, “WIC Program,” Pediatrics, Vol. 108, Issue 5, November 1, 2001, https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article-abstract/108/5/1216/63773/WIC-Program?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

[106] Ibid.

[107] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, “Importance of Social Determinants of Health and Cultural Awareness in the Delivery of Reproductive Health Care,” Committee Opinion, Number 729, January 2018, https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2018/01/importance-of-social-determinants-of-health-and-cultural-awareness-in-the-delivery-of-reproductive-health-care.

[108] CommunityRX could be programmed to include referrals to local WIC programs. Stacy Tessler Lindau et al., “Building and experimenting with an agent-based model to study the population-level impact of CommunityRx, a clinic-based community resource referral intervention,” PLOS Computational Biology, Vol. 17, No. 10, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009471.

[109] The clinic served 14,000 patients with more than 90 percent enrolled in Medicaid. Bryan Monroe et al., “Assessing and Improving WIC Enrollment in the Primary Care Setting: A Quality Initiative,” Pediatrics, Vol. 152, No. 2, August 2023, https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/152/2/e2022057613/192532/Assessing-and-Improving-WIC-Enrollment-in-the?autologincheck=redirected.

[110] Brittany Goldstein et al., “Integration of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in Primary Care Settings,” Journal of Community Health, September 2023, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10900-023-01287-5.

[111] Erin R. Hager et al., “Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity,” Pediatrics, Vol.126, No. 1, July 2010, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3146.

[112] Although an affirmative response to both questions increases the likelihood of food insecurity existing in the household, an affirmative response to only one question is often an indication of food insecurity and should prompt additional questioning. See Benjamin Gitterman et al., “Promoting Food Security for All Children,” Pediatrics, Vol 136, Issue 5, November 2015, https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/136/5/e1431/33896/Promoting-Food-Security-for-All-Children?autologincheck=redirected. USDA also has an 18-question measure to assess food insecurity with the Household Food Security Scale, which is the standard tool for research, but may not be necessary for making referrals to programs like WIC for food assistance. Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Security in the United States in 2013,” USDA, Economic Research Service, September 2014, https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=102075.

[113] For more information about tracking and coding systems, see Sheila Smith et al., “Medicaid Policies to Help Young Children Access Key Infant-Early Childhood Mental Health Services: Results From A 50-State Survey,” National Center for Children in Poverty at Bank Street Graduate School of Education, Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy, Center for Children and Families, and Johnson Policy Consulting, June 2022, p. 3, https://www.nccp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/NCCP-Medicaid-Brief_6.13.23-FINAL.pdf.

[114] Petry S. Urbi et al., “The Role of State Policy in Use of Z Codes to Document Social Need in Medicaid Data,” NORC, March 2022, https://www.norc.org/PDFs/Documentation%20of%20Social%20Needs%20in%202018%20Medicaid%20Data/The%20Role%20of%20State%20Medicaid%20Policy%20in%20Documentation%20of%20SDOH%20in%20Medicaid%20Data_032422.pdf.

[115] Bailit Health, “Addressing Health-Related Social Needs Through Medicaid Managed Care,” Health Foundation of South Florida, October 2022, https://www.shvs.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Addressing-HRSN-Through-Medicaid-Managed-Care_October-2022.pdf.

[116] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, “Screening Questions.”

[117] North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, “Healthy Opportunities.”

[118] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “Quality requirements under Medicaid managed care,” https://www.macpac.gov/subtopic/quality-requirements-under-medicaid-managed-care/.

[119] For more information about PIPs that focus on improvements in pregnancy, see Andy Schneider et al., “Medicaid Managed Care, Maternal Mortality Review Committees, and Maternal Health: A 12-State Scan,” Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy, Center for Children and Families, October 2023, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2023/10/16/medicaid-managed-care-maternal-mortality-review-committees-and-maternal-health-a-12-state-scan/.

[120] Division of TennCare, “2021 Update To The Quality Assessment And Performance Improvement Strategy,” https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/tenncare/documents/qualitystrategy.pdf.

[121] Minnesota Department of Human Services, “Contract for Prepaid Medical Assistance and Minnesota Care,” January 1, 2022, https://mn.gov/dhs/assets/2022-fc-model-contract_tcm1053-515037.pdf, For more information, see Stratis Health, “Performance Improvement Project (PIP): Healthy Start for Minnesota Children,” https://stratishealth.org/health-plan-performance-improvement-projects-pips/pip-healthy-start-for-minnesota-children/.

[122] Maggie Clark, “State Trends to Leverage Medicaid Extended Postpartum Coverage, Benefits and Payment Policies to Improve Maternal Health,” Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy, Center for Children and Families, March 20, 2023, https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2023/03/20/state-trends-to-leverage-medicaid-extended-postpartum-coverage-benefits-and-payment-policies-to-improve-maternal-health/.