BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Ryan Budget Again Includes a Medicaid Block Grant That Would Add Millions to the Ranks of the Uninsured and Underinsured

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s new budget again proposes to radically restructure Medicaid by converting it into a block grant and slash federal Medicaid funding by $810 billion over the next decade. He would also repeal health reform’s Medicaid expansion. All told, it would add tens of millions of Americans to the ranks of the uninsured and underinsured.

Repealing the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion means that up to 17 million people would no longer gain Medicaid coverage (17 million is the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of the number of people who would gain coverage if all states adopted the expansion). In addition, the large and growing cut in federal Medicaid funding that would result from the block grant would almost certainly force states to sharply scale back or eliminate Medicaid coverage for millions of low-income people who rely on it today.

Under the Ryan plan, the federal government would no longer pay a fixed share of states’ Medicaid costs. Instead, states would get a fixed dollar amount that would rise annually only with inflation and population growth.

- The block grant would cut federal Medicaid spending by $810 billion over the next ten years, from 2014-2023, according to Ryan’s budget plan. (It is conceivable that a small share of these cuts could come from the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which the Ryan budget would merge into its new Medicaid block grant.) This would be an estimated cut to federal Medicaid and CHIP funding of about 21 percent over ten years compared to current law and doesn’t count the loss of the large amount of additional funding that states would receive to expand Medicaid, as well as of the funding provided under a two-year extension of CHIP, in health reform.

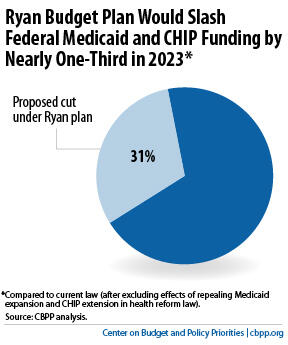

- Block grant funding amounts would fall further and further behind state needs each year. The annual increase in the block grant amounts would average about three percentage points less than Medicaid’s currently projected growth rate over the next ten years, which accounts for factors like rising health care costs and an aging population. Federal Medicaid and CHIP spending in 2023 would be $150 billion less — or 31 percent less — than what states would receive under current law, according to the Ryan budget (see graph). And the cuts would keep growing after 2023.

- The loss of federal funding would be even greater in years when enrollment or per-beneficiary health care costs rose faster than expected, such as during a recession or after the introduction of a new, breakthrough health care technology or treatment that improved patients’ health but increased cost. Currently, the federal government and the states share in those unanticipated costs; under the Ryan plan, states alone would pay them.

As CBO concluded when it analyzed the similar Medicaid block grant proposal from last year’s Ryan budget plan, “the magnitude of the reduction in spending . . . means that states would need to increase their spending on these programs, make considerable cutbacks in them, or both. Cutbacks might involve reduced eligibility . . ., coverage of fewer services, lower payments to providers, or increased cost-sharing by beneficiaries — all of which would reduce access to care.”

In making these cuts, states would likely use the expansive new flexibility that the Ryan plan would give them. For example, the plan would likely let states cap Medicaid enrollment and turn eligible people away from the program; under current law, states must accept all eligible individuals who apply. It also would likely let states drop certain benefits that people with disabilities or other special health problems need.

The Urban Institute estimated that Chairman Ryan’s block grant proposal of last year would lead states to drop between 14.3 million and 20.5 million people from Medicaid by 2022 (outside of the effects of repealing health reform’s Medicaid expansion). That would result in cuts in enrollment of between 25 percent and 35 percent. The Urban Institute also estimated that the block grant likely would have resulted in cuts in reimbursements to health care providers of more than 30 percent by 2022. There is no reason to think that this year’s proposal would result in cuts that are any less draconian.