- Home

- Social Security

- The Case For Updating SSI Asset Limits

The Case for Updating SSI Asset Limits

Raising or Eliminating Limits Would Reduce Administrative Burdens Without Dramatically Increasing Enrollment

The Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program for low-income elderly and disabled people has the strictest savings limits of any federal program. Eligibility is limited to people who have only $2,000 (or $3,000 for couples). This is not enough for beneficiaries to weather an emergency, let alone provide stability or save for the future. Administering the resource limit, often referred to as an asset test, is burdensome for both Social Security Administration (SSA) staff and for claimants. Policymakers should increase or even eliminate SSI’s resource limit amid growing bipartisan support to do so.

The resource limit is the leading cause of erroneous payments in the SSI program and leads to churn because beneficiaries who go even slightly over the outdated limit are suspended and then terminated. Beneficiaries who exceed the limit typically rack up thousands of dollars in overpayments that are extremely difficult to repay from their meager benefits. Additionally, SSA employees must administer these complex and inefficient rules amid a customer service crisis they are in due to underfunding. Because the value of the limit is not indexed to inflation — and hasn’t been updated in decades — its value erodes each year due to inflation. It is now only one-fifth of its 1972 value.

A higher limit would encourage — rather than penalize — saving and allow people to retain savings to use when they really need those resources. Research shows that having a financial cushion leads to greater economic security. A higher limit would also reduce administrative burdens, payment errors, and churn. And easing or eliminating the asset test would mean that more very low-income seniors and people with disabilities could get the income support they need to afford the basics and not be forced to first deplete modest savings. Policymakers have recognized the case for allowing greater savings and have increased or eliminated resource limits in other economic security programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid.

In this brief we analyze several ways to increase SSI’s resource limits, including raising them to $10,000 per beneficiary (as proposed in S. 2767 by Sens. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) and Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and H.R. 5408 by Reps. Brian Higgins (D-NY) and Brian Fitzpatrick (R-IL)), raising them to $100,000 per beneficiary (consistent with the limits in ABLE accounts, which don’t count against SSI’s resource limits), and eliminating resource limits (as other economic security programs have done). We also examine excluding retirement savings from SSI’s resource limits (as proposed in the SSI Restoration Act), in combination with each of these options.

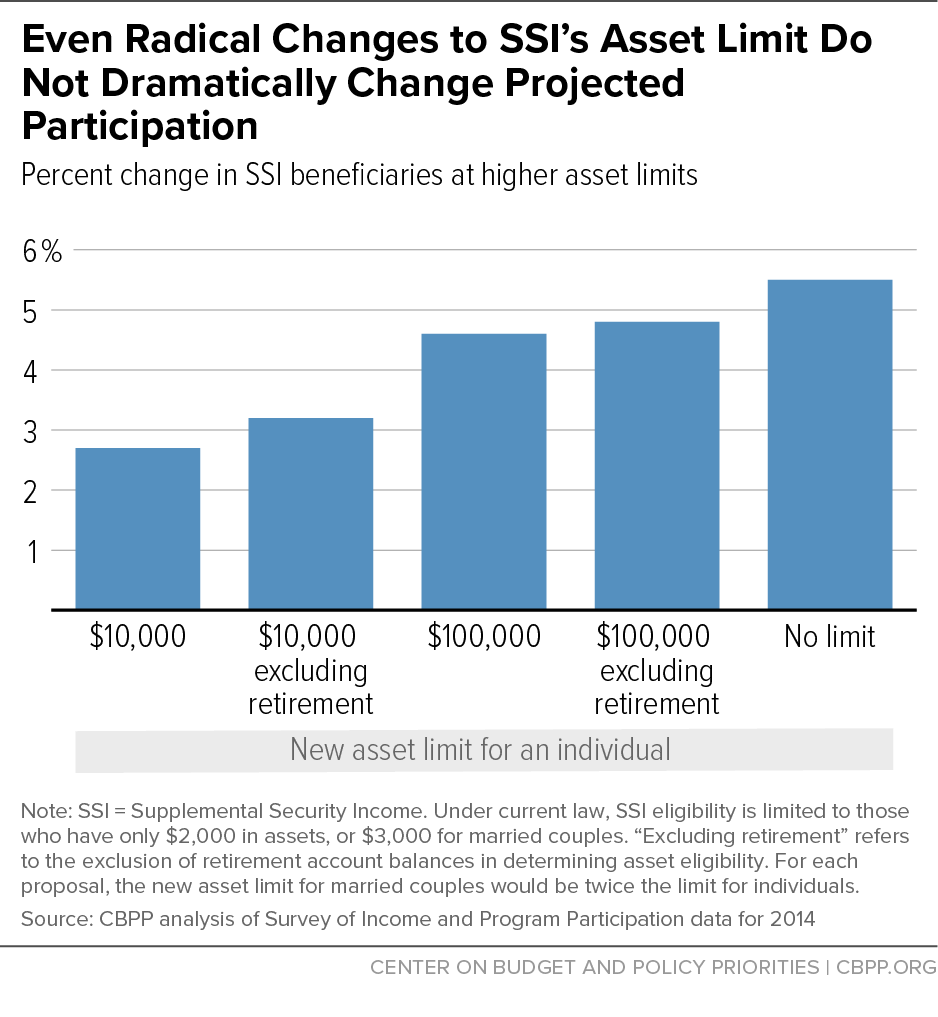

We find that increasing SSI’s resource limits to $10,000 per beneficiary would increase SSI participation by up to 3 percent. Increasing limits to $100,000 per beneficiary — a fiftyfold increase — would increase participation by about 5 percent, while eliminating limits would increase participation by about 6 percent. Excluding retirement accounts would only slightly increase participation. Even radical changes in SSI’s resource rules would not dramatically increase program participation, because few people who meet SSI’s other criteria have substantial savings. SSI beneficiaries must have very low incomes to qualify, and that means they have little margin for savings. In addition, they either have a disability that substantially limits their earnings, or they are over age 65.

SSI Provides Subsistence Benefits to Elderly and Disabled People Most in Need

Created in 1972, SSI provides monthly cash assistance to people who are disabled or elderly and have little income and few assets. Similar to the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program, commonly known as Social Security, SSI is administered by SSA. In May 2023, 7.5 million people collected SSI benefits. Most SSI beneficiaries — 85 percent — are eligible due to a severe disability (including blindness).[2]

Eligibility criteria for SSI are strict. All applicants must meet SSI’s stringent financial criteria, and applicants for disability benefits must also meet the same rigorous medical criteria used for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). About 60 percent of applications for SSI benefits were denied in 2018-2020, after all levels of appeal.[3] Those who qualify are subject to regular financial redeterminations to ensure continued compliance with SSI’s strict income and asset rules, and regular continuing disability reviews to ensure continued medical eligibility.

The basic federal SSI benefit is about three-fourths of the poverty line for a single person. Thus, while SSI alone is not enough to lift someone living independently above the poverty line, it reduces hardship and lessens the need for support from family members. But roughly half of all beneficiaries had incomes below the federal poverty line even with their SSI benefits in 2016.[4] In addition to providing modest cash benefits, SSI is an important pathway to health coverage, as beneficiaries in most states are automatically eligible for Medicaid. In addition to medical care, Medicaid provides essential long-term services and supports, allowing more elderly and disabled people to live in their homes and communities instead of in institutions.

SSI’s Resource Limits Have Stagnated at Low Levels for Decades

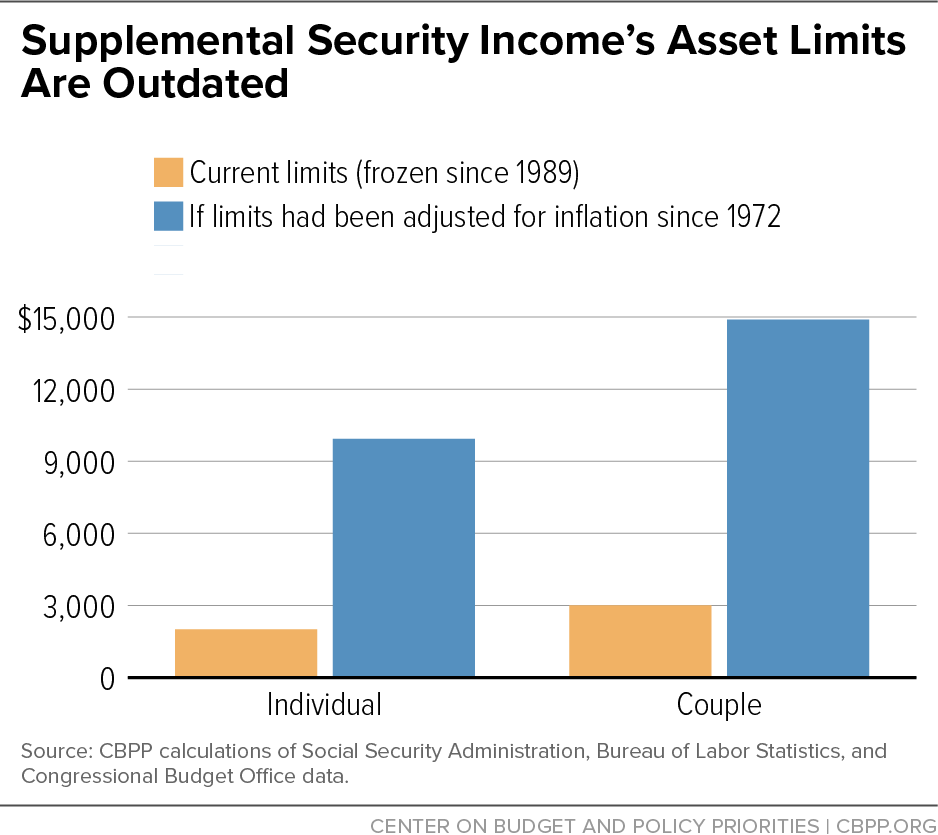

SSI has extraordinarily low resource limits. Applicants who exceed the limits are ineligible for any benefits from the program. Current beneficiaries who exceed the limits are suspended and then terminated from program participation if their savings remain above the limits, and they must repay any benefits paid while they are over the limit. SSI beneficiaries are limited to only $2,000 in assets of any kind. For married couples or two-parent families with SSI beneficiary children, the limit is $3,000, which creates a marriage penalty because the couple limit is 25 percent less than the limit for two individuals. (See Figure 1.) Countable resources include cash, bank accounts, retirement savings, stocks, mutual funds, savings bonds, life insurance, household goods, burial funds, and more, as well as the resources of parents, spouses, and immigration sponsors, in many cases. Primary residences and vehicles do not count against the resource limits.

SSI’s resource limits have changed little since the program’s establishment, even though the value of the limits has eroded dramatically. When policymakers created the program in 1972, they set resource limits of $1,500 for individuals and $2,250 for couples. Policymakers then gradually raised these resource thresholds between 1985 and 1989 to $2,000 for individuals and $3,000 for couples — the only resource increase since SSI was enacted over 50 years ago. Still, it only partially accounted for the effects of inflation up to that point. Had resource limits been indexed to inflation since 1972, when the law first passed, they would be $9,929 for an individual and $14,893 for a couple in 2023 — about five times as high as they are today.[5]

Most SSI beneficiaries are well under the resource limit. More than two-thirds of SSI beneficiaries have no savings at all, and about 92 percent have less than $500 in savings, according to our analysis. Few people with incomes low enough to qualify for SSI have many resources, because they have little margin for saving, research shows.[6]

Federal Treatment of Savings Has Evolved Since 1972

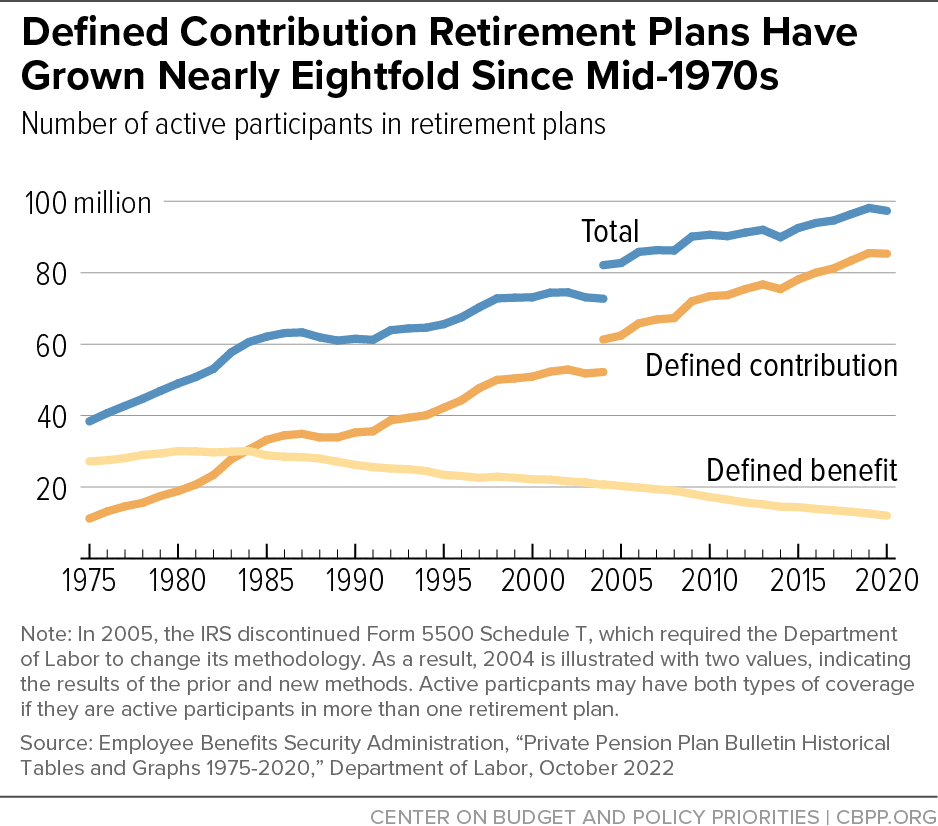

After SSI was enacted, federal policy began to encourage workers to accumulate savings to fund their retirements — even as it continued to penalize SSI beneficiaries if they managed to save anything at all, either for emergencies or for retirement. Individual retirement accounts (IRAs) were created in 1974 and 401(k)s in 1978 — after SSI and its resource limits were established. Today, far fewer workers are offered traditional workplace pensions, which don’t count against SSI’s resource limits, and far more are offered workplace retirement savings accounts, which do count against the resource limits.

The number of workers participating in “defined contribution” retirement accounts has risen nearly eightfold since the mid-1970s. As of 2020, there were seven times more defined contribution plans than traditional “defined benefit” plans, while the number of workers participating in defined benefit plans has dwindled (see Figure 2).[7] The recently enacted Securing a Strong Retirement Act of 2022 (known as SECURE 2.0) will automatically enroll more workers, including working SSI beneficiaries, into workplace retirement savings accounts.[8]

The Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Act of 2014 allows states to create tax-advantaged savings programs for eligible people with disabilities; these accounts do not count toward SSI’s resource limits and other economic security programs. SSI beneficiaries are allowed to hold up to $100,000 in ABLE accounts, essentially raising the resource limit by fiftyfold for participating beneficiaries. People who became disabled by age 26 are eligible for ABLE accounts. They account for about 44 percent of SSI beneficiaries, as many have developmental or congenital disabilities.[9] The accounts can be used by parents or other family members to provide for disabled relatives’ futures without jeopardizing their future eligibility for means-tested benefits. Funds from ABLE accounts may be used by beneficiaries to pay for a very broad set of “qualified disability expenses,” including housing, transportation, health, and basic living expenses.[10] The ABLE Age Adjustment Act was adopted as part of the SECURE 2.0 retirement savings package. It will expand eligibility for ABLE accounts to include people disabled by age 46, which would include a majority of SSI beneficiaries.

Though eligibility for ABLE accounts among SSI beneficiaries is broad — currently including nearly half of participants, and soon to include the substantial majority — participation is very limited. To date, only about 130,000 ABLE accounts have been set up, including for people who are not SSI beneficiaries.[11] That accounts for significantly less than 1 percent of SSI beneficiaries who are eligible under the current rules. A forthcoming study by the University of Chicago’s Inclusive Economy Lab sheds light on ABLE account usage and knowledge. Less than half of respondents heard about ABLE accounts, and among those who had, a majority misunderstood or underestimated their connection with SSI and its financial advantages.[12] Wealthier households were much more likely to know about ABLE accounts and to open them. This lack of awareness and understanding, as well as the additional administrative burden of opening a specialized account, limits the utility of ABLE accounts. By contrast, beneficiaries would not have to do anything to avoid penalties if SSI had higher resource limits.

Raising SSI’s Resource Limits Would Reduce Churn and Payment Errors

Administering the program’s extremely low resource limits creates significant challenges for applicants, beneficiaries, and SSA, which is underfunded and overworked. Applicants must answer dozens of questions about their resources and provide detailed documentation, which SSA employees review and process. Federal law requires SSA to verify applicants’ cash, bank accounts, stocks, mutual funds, savings bonds, property, life insurance, vehicles, household goods, burial funds, and more.[13] Because the resources of spouses, parents, and immigration sponsors can also be “deemed” to the beneficiary, SSA staff must examine those as well. The time spent producing and reviewing documents often delays the start of much-needed benefits; some applicants give up because they can’t produce paperwork that shows how little they own.

The requirement to prove their continued compliance contributes to “churn” in program participation. SSA must redetermine each beneficiary’s financial eligibility every one to six years and each time their circumstances change.[14] In addition, exceeding the resource limit is the leading cause of overpayments in SSI, which leads to future payments being cut or clawed back.[15] When a beneficiary goes over SSI’s resource test — even by a small amount — their entire benefit is not payable for that month. Typically, SSA lags in detecting and addressing overpayments, so beneficiaries are usually overpaid for months, racking up thousands of dollars that must be repaid. Most SSI beneficiaries have little to no other income, making it extremely difficult to repay these debts.

As a result of these strict resource rules, each year an average of 70,000 beneficiaries have their benefits suspended. Beneficiaries lose their entire benefit during suspensions, during which they must spend down their resources to reestablish eligibility, which can force beneficiaries to spend resources more quickly than is wise to ensure continued income assistance and the Medicaid benefits that come with it. After 12 months of suspension, they are terminated. On average, 40,000 beneficiaries have their benefits terminated each year for exceeding the resource limit, after which they must start the application process again.[16] In some cases, beneficiaries exceed the limit only temporarily — for example, by accruing interest in an emergency savings account that was previously below the limit. In other cases, they remain below the limit but can’t produce the necessary documentation to prove it.

Administering SSI’s complicated rules consumes a large portion of SSA’s budget and staff time, during a time when both are highly constrained. Administration of SSI absorbs 35 percent of SSA’s administrative outlays.[17] In contrast, 19 percent of SSA’s spending goes toward administering SSDI benefits, even though nearly 1.4 million more people receive those benefits than receive SSI.[18] At the same time, Social Security’s operating budget has been starved, even as demands on the agency increase. Between 2010 and 2023, the agency’s workload expanded dramatically, with the number of Social Security beneficiaries increasing by 12 million, or 22 percent.[19] However, the agency’s customer service budget shrank 17 percent after taking inflation into account, and its staff by 16 percent — to the lowest level in 25 years.[20]

If resource limits were updated, fewer beneficiaries would exceed them, reducing administrative burdens on both SSI beneficiaries and SSA staff. If limits were increased, SSA would continue using the same burdensome processes to determine a beneficiary’s resources. But significantly fewer beneficiaries would be subject to overpayments, suspensions, and terminations for exceeding the limits. Eliminating the resource limit would get rid of these burdens entirely, significantly simplifying administration.

Raising SSI’s Resource Limits Would Improve Income Security

SSI has the steepest savings penalty of any federal program, despite a large and growing body of evidence on the importance of savings. People with little to no savings are more likely to have subprime credit scores, struggle to pay bills, and have lower financial well-being.[21] They spend their money on current debts, such as unpaid bills. Having savings significantly reduces material hardship for low-income families.[22]

Living with a disability — as at least 85 percent of SSI beneficiaries do — also imposes additional costs. Households with a disabled member need about $18,000 more per year, on average, just to have the same standard of living as a similar household without a member with a disability, research shows.[23] Many of the additional costs of living with a disability are expensive and require savings to purchase, such as customized wheelchairs, home and automobile modifications, and other medical equipment not covered by Medicaid.

A higher asset limit would ensure that if an SSI applicant or current beneficiary has modest savings, they can qualify for SSI’s income assistance and they can keep those assets in hand to use when they need to, such as for expenses related to their health conditions, for repairs to cars or homes, or for family needs.

Raising SSI’s resource limits would also provide stability for beneficiaries who rely on other public benefits to meet their health care and housing needs. Going over the resource limit not only causes beneficiaries to lose SSI benefits, but also in many cases Medicaid, SNAP, and other benefits where eligibility is tied to receipt of SSI.

Policymakers Have Proposed Increases to SSI’s Resource Limits

The Supplemental Security Income Restoration Act of 2021, first introduced by Rep. Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ) (H.R. 3824) and Sen. Brown (S. 2065), would comprehensively update the SSI program. The bill would increase SSI’s resource limit for individuals to $10,000, restoring it to approximately the same amount as if it had been indexed to inflation since 1972; it would also increase the couple limit to $20,000, thus eliminating the marriage penalty. The bill would also automatically increase the limits each year with inflation and exclude retirement accounts from the resource test. It also included other provisions to raise benefits and to allow beneficiaries to keep more of their earnings and Social Security benefits, among other things.

In April 2022, Sens. Brown and Portman introduced the SSI Savings Penalty Elimination Act, including only the Supplemental Security Income Restoration Act provisions to raise the resource limits to $10,000 and $20,000 and index them to inflation.[24] Raising the program’s resource limits as proposed by the SSI Savings Penalty Elimination Act would restore the program to policymakers’ original intentions 50 years ago, by adjusting the individual threshold for the inflation that has occurred since 1972 and keeping its value intact in future years. It would also eliminate the marriage penalty.

The Supplemental Security Income Restoration Act also proposed to change the treatment of retirement savings accounts, which did not yet exist when SSI was established. Despite a dramatic shift in retirement income in the last 50 years — away from traditional pensions and toward individual accounts such as 401(k)s and IRAs — SSI’s resource test still penalizes low-income older and disabled people who hold retirement savings. Other programs, including SNAP, exclude retirement savings accounts from resource limits. Policymakers could similarly exempt retirement savings from the SSI resource test.

Additional Options to Improve SSI’s Savings Policy

Beyond the measures that policymakers have already introduced, there are a wide range of additional options to reduce or eliminate SSI’s penalties on savings. To better align with the intentions — if not the effect — of ABLE accounts, policymakers could also adopt a more generous $100,000 resource test. This would address the fact that only a small fraction of SSI beneficiaries eligible for ABLE accounts have managed to set them up. It would also afford the advantages of those accounts to beneficiaries who don’t have the knowledge or resources to open them by automatically allowing them to save more without losing eligibility.

Finally, policymakers could repeal SSI’s resource limits altogether. The Affordable Care Act prohibited states from applying resource limits to most Medicaid beneficiaries, including children, parents, pregnant people, and adults who became eligible for Medicaid under the law’s Medicaid expansion. In other economic security programs, federal policymakers have given states significant discretion to ease or eliminate resource limits, and nearly every state has used it. For example, most states now have no resource limits for their SNAP and Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) benefits.[25]

Higher Resource Limits Would Improve Access to SSI Benefits

If SSI’s resource limits were increased, more people would qualify for and maintain their benefits. Some applicants who would be rejected under current rules for having too much in savings would become eligible. Some current beneficiaries who would otherwise be suspended or terminated for having excess assets would be able to continue receiving benefits. Using Census Bureau data for 2014, we estimate that about 3 percent (224,000) more people would participate in SSI if the resource test were increased to $10,000 (and $20,000 for couples), as shown in Table 1 and Figure 3 below. If, in addition, SSI’s asset test excluded retirement accounts, about 39,000 more people (263,000 total) would participate.

Raising SSI’s resource test well above $10,000 — or eliminating it altogether — wouldn't dramatically affect participation, the estimates suggest. Even if the resource test were raised to $100,000 per beneficiary — 50 times the current limit for individuals — about 5 percent (380,000) more people would qualify for benefits. Raising the limit to $100,000 and excluding retirement accounts would expand participation by another 23,000 people (403,000 total). And eliminating the asset test altogether would expand participation by 6 percent (462,000 total).

Even large changes in SSI’s resource rules would not dramatically increase program eligibility, because few people who meet SSI’s other criteria have substantial savings. The large majority have a disability that substantially limits their earnings. For the same reasons, few SSI beneficiaries have managed to accumulate substantial retirement savings, so excluding retirement accounts from the asset test would make very little difference in program eligibility.

| TABLE 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated Number of New Beneficiaries at Higher SSI Asset Thresholds | ||||||

| $10,000 | $10,000 excluding retirement | $100,000 | $100,000 excluding retirement | No limit | ||

| Age group | ||||||

| Total, all ages | 224,000 (3%) | 263,000 (3%) | 380,000 (5%) | 403,000 (5%) | 462,000 (6%) | |

| Children, under 18 | 23,000 (2%) | 23,000 (2%) | 47,000 (4%) | 47,000 (4%) | 49,000 (4%) | |

| Adults, aged 18-64 | 154,000 (3%) | 176,000 (4%) | 248,000 (5%) | 257,000 (5%) | 298,000 (6%) | |

| Elderly, aged 65 and over | n/a | n/a | 86,000 (4%) | 99,000 (5%) | 115,000 (5%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 153,000 (4%) | 188,000 (5%) | 247,000 (6%) | 269,000 (7%) | 316,000 (8%) | |

| Black | 30,000 (2%) | 30,000 (2%) | 39,000 (2%) | 39,000 (2%) | 39,000 (2%) | |

| Asian | n/a | n/a | 30,000 (9%) | 30,000 (9%) | 36,000 (10%) | |

| Latino | 28,000 (2%) | 32,000 (2%) | 41,000 (3%) | 41,000 (3%) | 41,000 (3%) | |

Note: Percent change from current law is indicated in parentheses. “Excluding retirement” refers to the exclusion of retirement account balances in determining asset eligibility. For each proposal, the new asset limit for married couples would be twice the limit for individuals. Figures are rounded to the nearest 1,000. N/a indicates reliable data are not available due to small sample size. Figures may not sum to totals due to lack of reliable data and/or rounding. Latino may be of any race, and other races/ethnicities refer to those groups alone and not Latino. Latino includes all people of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin regardless of race. See the methodology appendix for more details.

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data for 2014

The impact of raising SSI’s resource limits varies by age and race. Higher asset limits would expand participation for elderly beneficiaries more than for younger beneficiaries, likely because older adults will have had more time to accumulate savings than younger beneficiaries. In addition, some older beneficiaries qualified based on age alone — not disability — so having a disability did not limit their ability to work and save, though given their current income, it is likely that they worked in low-paid jobs during their working-age years.

The impact of raising SSI resource limits also reflects the well-documented racial wealth gap. White and Asian American beneficiaries are more likely to become eligible for SSI under higher asset limits because they have higher savings, on average. Black and Latino people are less likely to have savings than white people — and, when they do, their value is substantially less. They are also less likely to be offered workplace retirement plans and likelier to work in low-paid jobs with little margin for savings.[26] That said, all SSI beneficiaries, regardless of race, must have very low incomes and assets to qualify.

Changing SSI’s Resource Limits Would Have Modest Impact on Projected Program Costs

Raising or even eliminating SSI’s resource limits would not dramatically increase program participation or costs. SSA’s actuaries have estimated that increasing the resource limits to $10,000 for individuals and $20,000 for couples would increase SSI costs by about $8 billion over ten years, or about 1 percent of program costs over that period.[27] They estimate that excluding retirement accounts from the resource test would have a “negligible” impact on SSI costs. Increased SSI participation would also increase Medicaid costs, because in most states SSI beneficiaries are automatically eligible for Medicaid.

Our participation estimates are based on a different model than the actuaries’ cost estimates, so they are not directly comparable. We would expect the percentage increase in participation and costs to be roughly proportional. However, it is likely that costs would not increase as much as participation. That is because people with assets of more than $2,000 generally have higher incomes and are more likely to be married than the average SSI beneficiary, because those factors allow more opportunity to save. The new beneficiaries in our simulation have somewhat higher average non-SSI income compared to current beneficiaries, which means their SSI benefits would be lower. SSI benefits are substantially reduced based on other sources of income — by $1 for every $2 of earnings, after the first $65 per month, and dollar-for-dollar after the first $20 of any other form of income, including Social Security benefits. A disproportionate share of the new beneficiaries in our simulation are married to other beneficiaries, which — because of SSI’s marriage penalty — results in a 25 percent lower benefit.

Few elderly or disabled people who meet SSI’s very low income criteria have much in savings, so even dramatically changing SSI’s resource rules doesn’t result in large participation or cost increases. Even fewer SSI beneficiaries have savings set aside specifically for retirement, so excluding retirement accounts from SSI’s resource rules would not be costly. However, it could be particularly helpful for working beneficiaries — a growing number of whom will be automatically enrolled in workplace retirement savings plans after the implementation of the SECURE 2.0 retirement savings legislation.

For a relatively small change in program costs, raising — or eliminating — SSI's resource limits could improve both beneficiaries’ well-being and the program’s efficiency. It would also ease administrative burdens, simplify program administration, and increase access for beneficiaries who are above the limits — or who are below the limits but have difficulty furnishing the paperwork to prove it.

Eliminating resource limits would markedly simplify applications and processing, reducing paperwork requirements and associated regulations. It would also reduce churn — a major problem for the more than 100,000 SSI beneficiaries who exceed the program’s low resource limits each year — which often triggers thousands of dollars of overpayments that are exceedingly difficult for beneficiaries to repay on their very low incomes. It would reduce the penalties for saving, especially for working beneficiaries. Finally, beneficiaries would no longer exceed the resource limits, thus reducing the number of errors.

Appendix: Methodology and Technical Note

Estimates in this brief are from Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis of data for 2014 from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The analysis is limited to individuals with countable income low enough to qualify for SSI. Spouses’ and parents’ income is deemed as indicated under program rules.

Participation in SSI requires applying to the program and meeting income, asset, age, and disability tests. To be eligible based on disability, SSI requires participants to demonstrate that they have a severe medical impairment that is expected to last at least 12 months or result in death, and (for adults) be unable to engage in any substantial gainful activity. The same disability test is used by Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI); people who do not meet SSI’s asset test may nonetheless be eligible for SSDI if they have a prior work history.

For people who meet SSI’s income test, our analysis uses SIPP data (and “probit” regression equations) to predict the combined likelihood of applying for SSI and/or SSDI and meeting the disability test. The resulting estimated population of would-be participants is then divided into those who meet SSI’s strict asset test under current law (i.e., simulated current participants) and those who would participate in SSI if their level of assets were allowed.

Predictors in this model include countable income and countable assets (both expressed using natural logarithms) and a variety of disability questions available on SIPP (such as “Does ... have a physical, mental or other health condition that limits the kind or amount of work they can do?” and “Does ... have a serious physical or mental condition or a developmental delay that limits ordinary activity?”), as well as race, education level, age, citizenship, health, and marriage status. All steps of the analysis are carried out separately for three age groups (under age 18, ages 18 through 64, and ages 65 and older) and omit people who are not income-eligible or for whom key income, asset, and program participation data on the survey file were not supplied by the household but were imputed by the Census Bureau. (Many SSI participants with imputed data in SIPP appear to have ineligible asset levels, a result that may to a large degree reflect inaccurate imputations.) The specific predictors differ by age group as some disability questions are asked to specific age ranges, and because predictors are dropped if they are not significantly predictive of participation for that age group at the 95 percent confidence level (p < 0.05).

For example, for the largest age group, those aged 18 to 64, this analysis uses the following equation to predict the likelihood of SSI participation for those who are income-eligible and who responded to all key survey questions (that is, data were not imputed):

Likelihood of SSI and/or SSDI participation =

0.18 ✖ (natural logarithm of SSI countable income)

- 0.04 ✖ (natural logarithm of SSI countable assets)

+ 0.02 ✖ (age)

+ 0.79 ✖ (reported being prevented from work)

+ 0.28 ✖ (reported having difficulty doing errands alone)

- 0.19 ✖ (reported having serious difficulty walking or climbing stairs)

+ 0.37 ✖ (reported having at least one of six core disability measures: hearing, seeing, cognitive, ambulatory, self-care, and/or independent living)

+ 0.62 ✖ (reported having a physical, mental, or other health condition that limits the kind or amount of work they can do)

+ 0.53 ✖ (reported receiving income due to a disability or health condition at any time during the reference period)

- 0.32 ✖ (educational level categorized into less than a high school diploma, high school diploma to associate degree, and bachelor’s degree or more)

- 0.37 ✖ (married)

- 0.94 ✖ (not a U.S. citizen)

The prediction is converted into a probability of participating in SSI and/or SSDI for those considered income eligible, and that probability is applied to each individual’s monthly survey weights. The resulting population of simulated current and would-be SSI participants (identified by survey weights multiplied by the probability of participating in SSI and/or SSDI) is divided into those with countable positive assets below $2,000 ($3,000 if married), others below $10,000 ($20,000 if married), others below $100,000 ($200,000 if married), and those with $100,000 ($200,000) or more. Those with assets below $2,000 ($3,000) are simulated to be current SSI participants. A final weighting adjustment (which mainly serves to counteract the effect of dropping imputed data, and which consists of a single adjustment factor for each age group, applied to all simulated participants or potential SSI participants) brings the number of simulated current participants in each age group to actual SSI totals for 2014 from administrative records. The final weighting adjustment — multiplying by 1.51 — brings the simulated participants aged 18 to 64 under current law from 3.25 million to 4.91 million.

Note that inaccuracies in reported income, assets, and SSI and SSDI program participation, and other imperfections in the modeling, may affect the size and composition of the simulated eligibility group. A 2020 analysis from the Census Bureau on the dataset used for this analysis suggests that bias may under- or over-estimate participation in government programs, earnings, and income among other variables.[28] The inclusion of logged assets in the predictive model means that we are implicitly assuming that people with higher assets are less likely to apply and participate, an assumption that fits our data on current SSI and SSDI participants well but is somewhat speculative with regard to future SSI participants.

Six questions are used in the Census Bureau’s major surveys to measure disability. The Survey on Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and Current Population Survey also ask additional disability questions. These survey questions cannot fully capture the medical-vocational criteria used to determine SSI disability eligibility. For example, they do not ask about the specific diagnosis, expected length of the disability, its severity, or the respondent’s ability to perform substantial gainful activity. As a result, our estimates of who meets SSI’s disability criteria are necessarily less precise than those of who meets its financial criteria.

Some studies use different data. For example, an Institute of Medicine study uses SSA administrative data and the National Survey of Children’s Health, which asks about specific diagnoses.[29] However, these data are not available to non-governmental researchers. Though using these data has advantages, it also has significant limitations in estimating who meets SSI and SSDI’s strict disability definition.

SIPP is a leading source of data on income and wealth, which allowed us to closely replicate SSI’s disregards when determining financial eligibility. Our definitions of “countable income” and “countable assets” take into consideration SSI’s disregards, such as the value of the home serving as the principal place of residence, SSI’s earned and unearned income exclusions, and many others.

End Notes

[1] We are grateful to AARP for funding this research. The views expressed are solely those of the authors and should not be attributed to AARP. We thank Joel Eskovitz and Jim Palmieri for helpful comments on an earlier version of this report.

[2] Social Security Administration (SSA), “SSI Monthly Statistics, May 2023,” June 2023, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_monthly/index.html.

[3] CBPP, “Policy Basics: Supplemental Security Income,” updated February 21, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/supplemental-security-income.

[4] Matt Messel and Brad Trenkamp, “Characteristics of Noninstitutionalized DI, SSI, and OASI Program Participants, 2016 Update,” April 2022, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/rsnotes/rsn2022-01.html.

[5] CBPP calculations of SSA, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office data.

[6] Paul S. Davies et al., “Modeling SSI Financial Eligibility and Simulating the Effect of Policy Options,” Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 64, No. 2, September 2002, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v64n2/v64n2p16.pdf.

[7] Employee Benefits Security Administration, United States Department of Labor, “Private Pension Plan Bulletin Historical Tables and Graphs, 1975-2020,” October 2022, https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/EBSA/researchers/statistics/retirement-bulletins/private-pension-plan-bulletin-historical-tables-and-graphs.pdf.

[8] Securing a Strong Retirement Act of 2022, H.R. 2954, https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2954.

[9] William R. Morton and Kirsten J. Colello, “Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Programs,” IF10363, Congressional Research Service, March 17, 2017, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10363.

[10] SSA Program Operations Manual System (POMS), SI 01130.740, Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Accounts, https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0501130740.

[11] National Association of State Treasurers, ABLE (Achieving a Better Life Experience), https://nast.org/able/.

[12] Guglielmo Briscese, Michael Levere, and Harold Pollack, “Improving Financial Security for People with Disabilities through ABLE Accounts,” presentation at Household Finance Research Seminar, February 16, 2023.

[13] SSA, Application for Supplemental Security Income (SSI), https://www.ssa.gov/legislation/Attachment%20for%20SSA%20Testimony%207_25_12%20Human%20Resources%20Sub%20Hearing.pdf.

[14] SSA, “Understanding Supplemental Security Income Redeterminations — 2023 Edition,” https://www.ssa.gov/ssi/text-redets-ussi.htm.

[15] SSA, Agency Financial Report for Fiscal Year 2022, Other Reporting Requirements, https://www.ssa.gov/finance/2022/Other%20Reporting%20Requirements-.pdf.

[16] SSI Annual Statistical Report, 2021, Tables 76 and 77, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/ssi_asr/2021/sect11.html.

[17] SSA, “Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees Fiscal Year 2024,” March 2023, https://www.ssa.gov/budget/assets/materials/2024/FY24-JEAC.pdf.

[18] Ibid.

[19] CBPP calculations of SSA, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and Congressional Budget Office data; SSA, “Number of beneficiaries receiving benefits on December 31, 1970-2022,” https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/OASDIbenies.html.

[20] SSA, “Annual Statistical Supplement, 2022,” Table 2.F3, December 2022, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2022/2f1-2f3.html#table2.f3; Kathleen Romig, “Long Overdue Boost to SSA Funding Would Begin to Improve Service,” CBPP, March 30, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/long-overdue-boost-to-ssa-funding-would-begin-to-improve-service.

[21] Caroline Ratcliffe et al., “Emergency Savings and

Financial Security Insights from the Making Ends Meet Survey and Consumer Credit Panel,” CFPB Office of Research Data Point No. 2022-01, March 2022, https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_mem_emergency-savings-financial-security_report_2022-3.pdf.

[22] Signe-Mary McKernan et al., “Building Savings, Ownership, and Financial Well-Being,” Urban Institute, April 9, 2020, https://www.urban.org/research/publication/building-savings-ownership-and-financial-well-being.

[23] Zachary Morris et al., “The Extra Costs Associated with Living with a Disability in the United States,” October 14, 2020, https://www.nationaldisabilityinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/extra-costs-working-paper.pdf.

[24] SSI Savings Penalty Elimination Act, S. 2767, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2767 and H.R. 5408, https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/5408?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22ssi+savings+penalty+elimination+act%22%7D&s=2&r=1.

[25] Prosperity Now Scorecard, Financial Assets and Income, Asset Limits in Public Benefit Programs, https://scorecard.prosperitynow.org/data-by-issue#finance/policy/savings-penalties-in-public-benefit-programs.

[26] Alicia H. Munnell and Christopher Sullivan, “401(k) Plans and Race,” IB#9-24, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, November 2009, https://crr.bc.edu/briefs/401k-plans-and-race/.

[27] SSA, Office of the Chief Actuary, “Estimated Change in Federal SSI Program Cost from Enacting S. 2065, the ‘Supplemental Security Income Restoration Act of 2021,’ introduced on June 16, 2021, by Senators Brown, Warren, Sanders, and others,” July 16, 2021, https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/solvency/SSIRestorationAct_20210716.pdf.

[28] Anthony G. Tersine, Jr., Memorandum to Carolyn M. Pickering, Survey Director, Associate Director for Demographic Programs, August 17, 2020, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/sipp/tech-documentation/complete-documents/2014/2014_SIPP_Wave_2_Nonresponse_Bias_Report.pdf.

[29] Thomas F. Boat and Joel T. Wu, “Mental Disorders and Disabilities Among Low-Income Children,” National Academies Press, October 28, 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK332882/.

More from the Authors