BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Retirement Savings Bill Should Improve Financial Security for Low-Income Elderly, Disabled People

Policymakers can correct one of the most egregious anti-savings provisions in federal law by raising Supplemental Security Income (SSI) asset limits as part of upcoming retirement savings legislation.

SSI, which provides monthly cash assistance to older and disabled people with very low incomes, limits beneficiaries’ savings to a mere $2,000 (or $3,000 for a couple); anyone exceeding these limits is disqualified from the program. When the Senate Finance Committee considers the House-passed SECURE 2.0 bill, it should add a new bipartisan proposal from Senators Rob Portman and Sherrod Brown to raise those limits to $10,000 and $20,000, respectively, and index them to inflation going forward. These changes would allow more elderly or disabled people with modest savings and very low incomes to get needed support through SSI.

Despite growing recognition by policymakers and analysts that having an asset cushion boosts economic security, SSI’s limits continue to penalize saving. When creating SSI in 1972, policymakers set asset limits that let beneficiaries have some savings to cover the cost of emergencies. But they haven’t updated those limits since 1989, even to adjust for inflation, leaving beneficiaries at risk in the event of an accident, unexpected repair bill, or other expense. SSI benefits are very low — only three-fourths of the poverty line — leaving 4 in 10 beneficiaries in poverty even with their benefits.

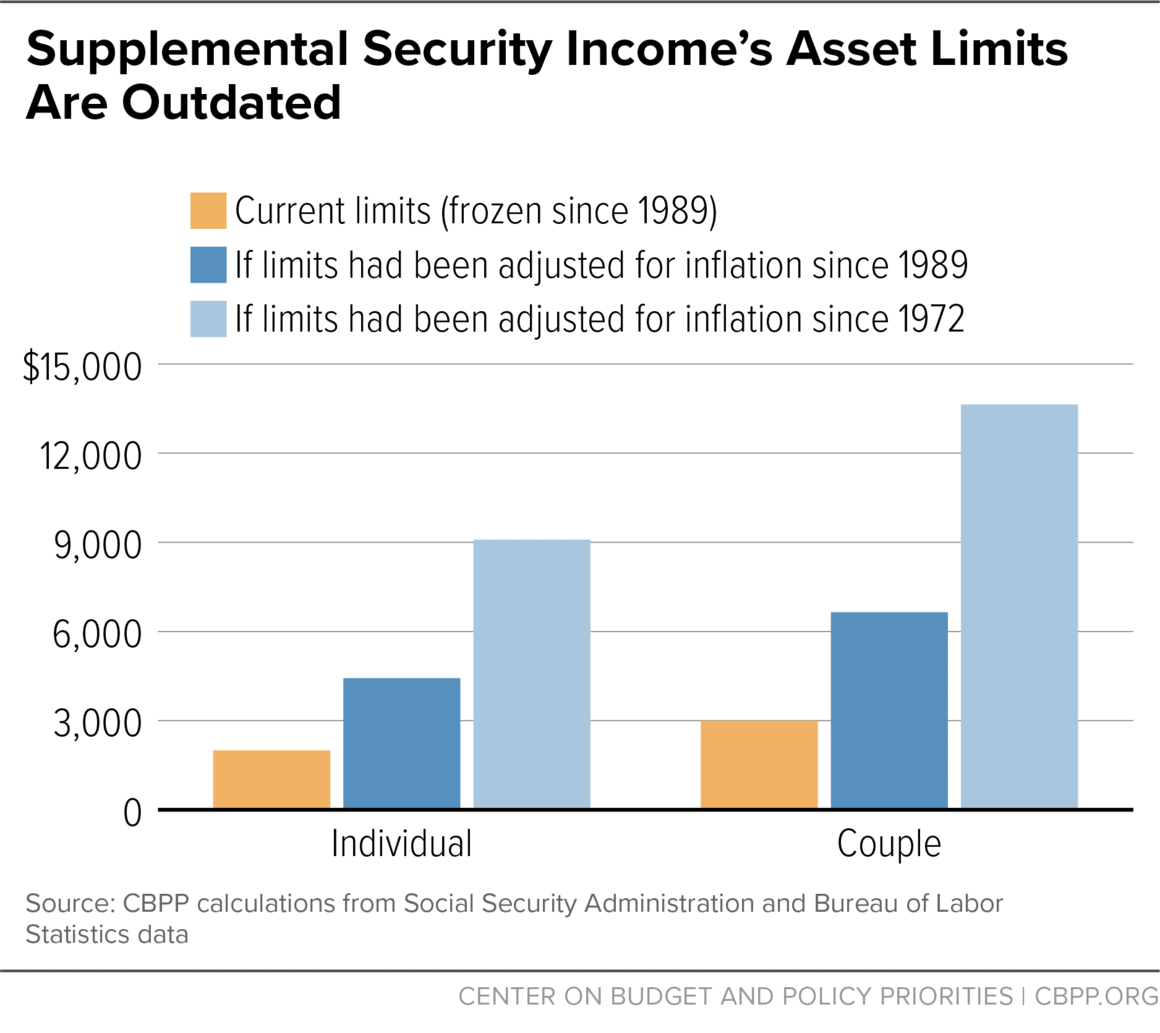

Had SSI’s asset limits been indexed to inflation since 1989, they’d be more than twice as high as they are today. And had they been indexed since 1972, they’d be more than four times as high. (See graphic.) Each year, the limits erode further in value due to inflation.

The Portman-Brown proposal would update the individual asset limit to account for past inflation and eliminate the marriage penalty in the couples’ limit, which is now only 50 percent higher than the individual limit. The updated limits in the bill would still be well below the net worth of a typical household, a recent analysis by the Niskanen Center shows.

Though very few people with incomes low enough to qualify for SSI have many assets (or any at all), administering the program’s extremely low asset limits creates significant challenges for applicants, beneficiaries, and the Social Security Administration (SSA), which is already underfunded and overworked.

Applicants must answer dozens of questions about their resources and provide detailed documentation, which SSA employees must review and process. The law requires SSA to verify applicants’ cash, bank accounts, stocks, mutual funds, savings bonds, property, life insurance, vehicles, household goods, burial funds, and more, as well as the resources of their parents and spouses in many cases. The time spent producing and reviewing documents often delays the start of much-needed benefits. Some applicants give up because they can’t produce paperwork that shows how little they actually own.

Asset tests also impose burdens on SSI beneficiaries. The requirement to prove their continued compliance contributes to “churn” in program participation and can lead to improper payments. SSA must redetermine each beneficiary’s financial eligibility every one to six years and each time their circumstances change. Exceeding the asset limit is the leading cause of overpayments in SSI, causing harm when future payments are cut or clawed back.

Each year an average of 70,000 beneficiaries have their benefits suspended and another 40,000 have their benefits terminated for failing to adhere to the asset rules. In some cases, beneficiaries exceed the limits only temporarily — for example, by accruing interest in an emergency savings account that was previously under the limit. In other cases, they remain below the limit but can’t produce the necessary documentation to prove it. When benefits are suspended, beneficiaries must reestablish eligibility, and when they are terminated, they must start the application process again from the beginning.

If asset limits were set at a more reasonable level, fewer beneficiaries would exceed them. This would significantly reduce the number of overpayments, suspensions, and terminations and reduce burdens on both SSI beneficiaries and SSA staff. It would also enable more low-income people who need support to qualify for SSI benefits, particularly seniors, who are likelier to have some savings. SSI improvements are especially important for people of color, who make up a majority of beneficiaries.

Raising the asset limits would also let SSI beneficiaries build more adequate emergency savings. Since exceeding the limit can cause the loss of not just SSI cash benefits but also in some cases Medicaid, housing assistance, and other benefits where eligibility is tied to receipt of SSI, a prudent beneficiary will avoid saving too much. Savings and assets, however, play an important role in improving economic stability for low-income individuals, a large body of research shows, including a new analysis by JPMorgan Chase that recommends raising SSI’s asset limits.

In other economic security programs, federal policymakers have given states significant discretion to ease asset limits, and nearly every state has used it to increase asset limits or eliminate them altogether. These programs include the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). Every state except Arkansas and Missouri has eliminated asset limits in at least one of those programs, and seven states — Alabama, Colorado, Hawai’i, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, and Ohio — have eliminated them in all three. And the Affordable Care Act prohibited states from applying asset limits to most Medicaid beneficiaries, including children, parents, pregnant women, and adults who became eligible for Medicaid under the law’s Medicaid expansion.

SSI’s asset limits badly need updating. The SECURE 2.0 bill should raise them, as Senators Portman and Brown have proposed. Congress should seize the opportunity.