BEYOND THE NUMBERS

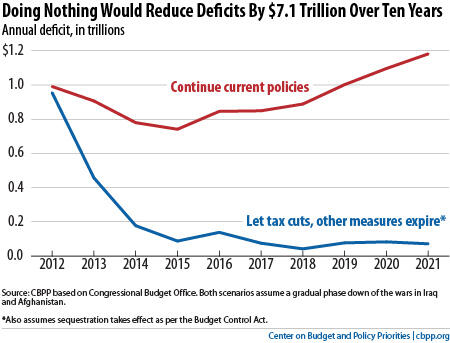

E. J. Dionne’s Washington Post column today cites my estimate that we could reduce deficits by $7.1 trillion over the next decade simply by letting various temporary tax and spending policies expire on schedule.

CBPP doesn’t favor letting all of these policies expire or using all of the savings for deficit reduction. Still, the massive potential savings from inaction show why the nation would be better off if the “supercommittee” fails to reach a deficit-reduction deal than if it reaches a deal that is highly unbalanced and calls for the largest sacrifices from those least able to bear them.

Below is the memo I sent E. J. Dionne explaining my $7.1 trillion estimate, which he has also reprinted in his blog.

Budget experts agree that federal budget deficits and debt will grow to unacceptable levels in coming years and decades if policymakers do not make changes in current policies. What’s also true, but less widely discussed, is that, under current law, changes in current policies that would reduce deficits to acceptable levels will take place unless Congress intervenes to stop that from occurring. That is, Congress can reduce deficits to acceptable levels simply by not passing certain new legislation.

The projections of growing deficits and debt under current policies assume that Congress will enact laws to extend a number of current tax and spending policies that are scheduled to expire. They also assume that the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (the “Supercommittee”) will not produce $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years and that Congress will then enact legislation to prevent the automatic across-the-board spending cuts (the “sequestration,” which is supposed to occur if the Joint Committee fails to achieve its goal) from taking effect.

What would happen, however, if Congress did not do any of those things? Deficits would be more than $7.1 trillion lower over the next 10 years, and the budget would be nearly balanced in 2021. The savings from such inaction would be:

- $3.3 trillion from letting temporary income and estate tax cuts enacted in 2001, 2003, 2009, and 2010 expire on schedule at the end of 2012 (presuming Congress also lets relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax expire, as noted below);

- $0.8 trillion from allowing other temporary tax cuts (the “extenders” that Congress has regularly extended on a “temporary” basis) expire on schedule;

- $0.3 trillion from letting cuts in Medicare physician reimbursements scheduled under current law (required under the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate formula enacted in 1997, but which have been postponed since 2003) take effect;

- $0.7 trillion from letting the temporary increase in the exemption amount under the Alternative Minimum Tax expire, thereby returning the exemption to the level in effect in 2001;

- $1.2 trillion from letting the sequestration of spending required if the Joint Committee does not produce $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction take effect; and

- $0.9 trillion in lower interest payments on the debt as a result of the deficit reduction achieved from not extending these current policies.

Related Posts: