BEYOND THE NUMBERS

We released a brief analysis of the President’s corporate tax reform framework this morning. Here’s the opening:

The Administration has advanced a coherent framework for corporate tax reform that could lead to a more efficient corporate tax regime. The framework’s main weakness is that it seeks no deficit-reduction contribution from corporate tax reform, aiming only for revenue neutrality.

Given the nation’s serious long-term budget problems and the painful sacrifices that policymakers will have to impose to put the budget on a sustainable path, it is imperative that all parts of the budget be on the table. A key test of well-designed corporate tax reform, therefore, is that it contributes to long-term deficit reduction; the Administration’s framework falls short in this critical area. The framework also lacks detail on how to achieve its revenue-neutrality goal.

To its credit, the Administration’s framework addresses the other key tests of successful corporate tax reform. It would impose a minimum tax on the overseas profits of U.S.-based firms to correct the tax code’s tilt in favor of overseas investments and to reduce corporations’ incentives to shift domestic profits to tax havens. It calls for reducing the tax code’s bias toward debt financing of corporate investments and for achieving greater parity between the tax treatment of large businesses with different corporate structures. Finally, it calls for the elimination of certain industry-specific tax subsidies.

In analyzing this and other corporate tax reform proposals, we measure them against six tests outlined in our newly updated report. A well-designed corporate tax proposal should:

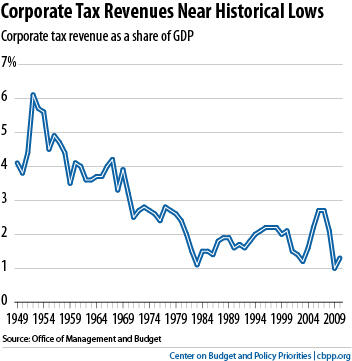

- Contribute to long-term deficit reduction. Corporate tax revenues are now at historical lows as a share of the economy (see graph), at a time when the nation faces deficits and debt that are expected to grow to unsustainable levels. Although the top statutory corporate tax rate is high, the average tax rate — that is, the share of profits that companies actually pay in taxes — is substantially lower because of the tax code’s many preferences (deductions, credits and other write-offs that corporations can take to reduce their taxes). Moreover, when measured as a share of the economy, U.S. corporate tax receipts are actually low compared to other developed countries. All parts of the budget and the tax code, including corporate taxes, should contribute to deficit reduction. Well-designed corporate tax reform can improve economic efficiency and help on the deficit-reduction front at the same time.

- Reduce the tax code’s bias toward overseas investments. U.S. multinationals pay much lower taxes on profits from their overseas investments than on profits from their domestic investments. That gives corporations a strong incentive to shift economic activity and income from the United States to other countries. Policymakers should address the features of the corporate tax code that allow so much business activity to escape taxation and that favor foreign investments over domestic ones.

- Improve economic efficiency by reducing special preferences. The corporate tax code taxes different kinds of corporate investments at very different rates. This “unlevel playing field” encourages businesses to choose among investments in substantial part based on their tax benefits, instead of making those decisions based entirely on investments’ real economic value. Policymakers should level the playing field through corporate tax reform.

- Provide more neutral treatment of corporate and non-corporate businesses. Over time, various policy changes have made it easier for companies to enjoy the benefits of corporate status without being subject to the corporate income tax. Reform should reflect the guiding principle that firms engaging in similar activities and enjoying similar legal benefits should be taxed at similar rates.

- Reduce the tax code’s bias towards debt financing. The current corporate tax code encourages corporations to finance their investments with debt (e.g., by issuing bonds) rather than equity (e.g., by selling stock). This encourages corporations to rely excessively on debt, which, as the recent financial crisis demonstrated, poses risks for both the firms and the broader economy. The tax code should be more even-handed in treating these two types of financing.

- Take specific steps to discourage tax sheltering. If policymakers lower the statutory corporate tax rate to well below the top individual tax rate, they should also establish safeguards to prevent high-income individuals from sheltering their income in corporations in order to pay taxes at a lower rate.