BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Many conservatives, including the Wall Street Journal editorial page and House Ways and Means Chairman Paul Ryan, are touting new research claiming that the expiration of emergency federal unemployment insurance (UI) benefits at the end of 2013 led employers to create 1.8 million additional jobs in 2014. The same researchers previously claimed that the existence of emergency federal jobless benefits explained most of the persistence of high unemployment in the recovery from the Great Recession.

These findings merit considerable skepticism.

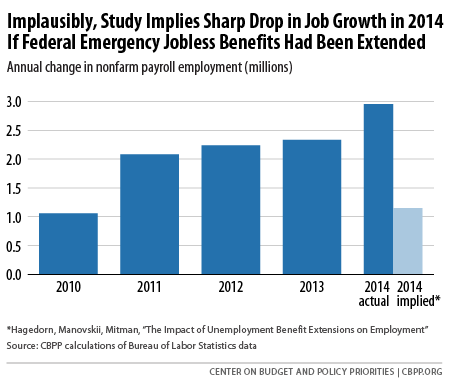

Let’s start with the 1.8 million net new jobs. The implication is that if lawmakers had renewed federal UI for 2014 instead of letting it expire, employers would have added fewer than 1.2 million jobs to their payrolls in 2014 instead of the nearly 3 million they did add. That would have been about half the 2.3 million jobs added in 2013 (see chart); it’s also well below the pace earlier in the recovery in 2011 and 2012, when many more people were receiving federal UI benefits. It’s hard to believe that continuing federal UI at 2013 levels would have so completely derailed the jobs recovery in 2014.

Dean Baker offers a further reason to doubt this finding. It falls apart when one uses a different dataset that’s arguably superior for estimating job growth.

The study takes advantage of the fact that the maximum number of weeks of federal UI available in a state in 2013 depended on the state’s unemployment rate to infer the employment effect of losing more versus fewer weeks of benefits in 2014 after federal UI ended. It relies on state and local data from the Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), whose concepts and definitions BLS says “come from the Current Population Survey (CPS), the household survey that is the official measure of the labor force for the nation.” Those data are necessary for examining unemployment and labor force participation, but labor market analysts usually rely on the BLS survey of employers when evaluating trends in job creation.

To illustrate their findings, the researchers divide states into two groups: those that lost a large number of weeks of federal UI and those that lost a smaller number. They find that employment accelerated more in 2014 in the former than in the latter, implying that additional weeks of federal UI were a drag on job creation.

Baker did the same comparison using the survey of employers and found the opposite. Job growth after the federal program expired was faster in the group of states that lost a smaller number of weeks.

The fact that using employer-based data reverses the key finding that UI kills jobs is hardly a testament to the claim’s robustness.

To be sure, the researchers’ conclusions on how UI affects job creation rest on more sophisticated analysis than the simple comparisons described here. But, as I’ll explain in a follow-up post, their research has met with considerable skepticism from other labor market experts. And the prevailing wisdom that any adverse employment effects from UI are small continues to, well, prevail.