BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Sequestration Would Deny Nutrition Support to At-Risk Low-Income Women and Children

Update April 11: The paper this post is based on has been updated and can be found here.

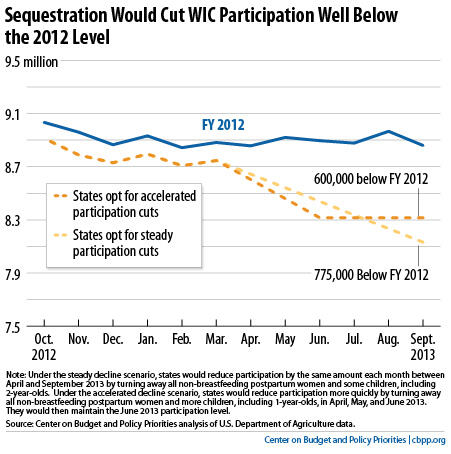

As we explain in a new paper, some 600,000 to 775,000 low-income women and children who are eligible for WIC — the highly effective nutrition program that serves roughly 9 million low-income women and children — will be turned away by the end of the fiscal year if the budget cuts known as “sequestration” take effect as scheduled on March 1.

That would break a longstanding and laudable bipartisan practice, dating back to 1997, of providing sufficient funding to ensure that WIC can serve all eligible low-income pregnant women, infants, and young children who apply.

WIC faces a $340 million funding cut compared to the level provided under the Continuing Resolution now in place — or $699 million less than the program received in fiscal year 2012.

Cuts of that magnitude would force states — which implement WIC under the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s oversight — to make harsh choices about how to cut their caseloads. The more rapidly that a state WIC program reduces the number of participants, the quicker the state will accumulate savings and the less steep the caseload reductions that they’ll need in the final months of the fiscal year (see chart).

Under one scenario, states might cut participation rapidly in April, May, and June — turning away all non-breastfeeding postpartum women and most children whose inadequate diets place them at nutritional risk (but who have not yet developed a medical condition), including many children who are only 1 year old. Using this approach, many state WIC programs would achieve enough savings by June that they could begin to ease eligibility restrictions and maintain the June participation level in July, August, and September. This would result in about 600,000 fewer participants nationally in the final months of the year than the average fiscal year 2012 participation level.

Alternatively, states could take a steady path of reducing the caseload by the same amount each month, turning away approximately 100,000 women and children monthly — including all non-breastfeeding postpartum women, about two-thirds of the 2-year-olds, and all children aged 3 and 4 at nutritional risk due to an inadequate diet. By September, the WIC caseload would be 775,000 less than the average caseload in fiscal year 2012.

The negative effects of either option would likely reverberate beyond September — and recent research suggests that the consequences of low-income pregnant women, infants, and very young children losing food assistance could be significant and long-lasting.

The nuances of the states’ policies may be poorly understood, which could affect pregnant women and infants even if states continue to serve them. For example, if states turn away non-breastfeeding postpartum women, word could spread that women can no longer get WIC benefits, and eligible pregnant or breastfeeding women may unwittingly miss out on benefits. And even if policymakers provide adequate WIC funding for 2014, local WIC programs would not be able to hire staff and spread the word rapidly enough to begin serving all eligible applicants again at the start of the fiscal year in October.