BEYOND THE NUMBERS

If you are wondering what’s behind the stubbornly high poverty rate, which has remained virtually frozen for the last two years despite continued economic growth, one thing is unemployment insurance (UI). Not too much UI — too little. As our new report explains, if the UI system hadn’t weakened, poverty would have fallen in the last two years, instead of remaining stalled at around 15 percent. And UI will shrink further in just a few months unless Congress acts.

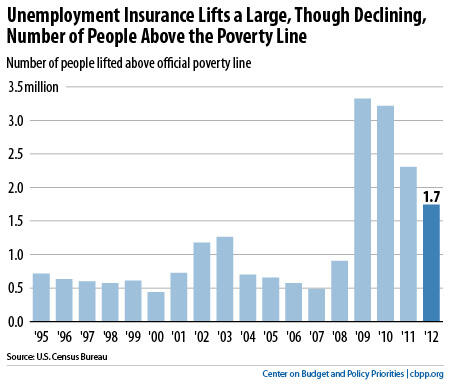

UI benefits kept 1.7 million people — jobless workers and their families — above the poverty line in 2012, according to Census figures. That’s a lot of people. Yet it’s 600,000 fewer than in 2011 and 1.5 million fewer than in 2010 (see graph).

To be sure, the decline partly reflects some good news: fewer workers are jobless so fewer are eligible for benefits. But that only explains a little of the drop. The number of unemployed workers fell by 16 percent from 2010 to 2012 (and some of that decline represents jobless workers who gave up looking for work, rather than those who got jobs). The number of people whom UI protected from poverty plunged by nearly three times as much: 46 percent.

The big reason is the dwindling likelihood that an unemployed worker will receive UI. The number of UI recipients for every 100 unemployed workers fell from 67 in 2010 to 57 in 2011 and 48 in 2012.

In fact, while the number of jobless workers has been falling, the number of jobless workers who receive no UI benefits has been rising and is higher now than at the bottom of the recession in 2009.

The share of unemployed workers getting UI fell for several reasons. First, the length and depth of the jobs slump has left many workers unable to find work before their UI benefits run out. Second, several states have cut the number of weeks of regular, state-funded UI benefits.

But another major reason is that in 2012, policymakers provided fewer weeks of federal UI benefits, which go to long-term unemployed workers. They cut the number of weeks of federal UI benefits provided through one UI program (Emergency Unemployment Compensation) and chose not to take steps they had taken in the past to continue access to another federal UI program (Extended Benefits), which as a result is essentially no longer available.

Congress’ role is especially important because what’s left of federal UI is scheduled to expire at the end of December unless lawmakers prevent it. My colleague Chad Stone will discuss this in an upcoming post.