BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Tax Expenditures a Good Target for Deficit-Reduction Efforts

Testifying before the Senate Budget Committee on tax reform and deficit reduction, Center Executive Director Robert Greenstein stated recently that reforming tax expenditures — i.e., spending that is delivered through the tax code rather than through public programs — can reduce deficits, promote economic efficiency, and make the tax code more progressive at the same time. Here are some excerpts:

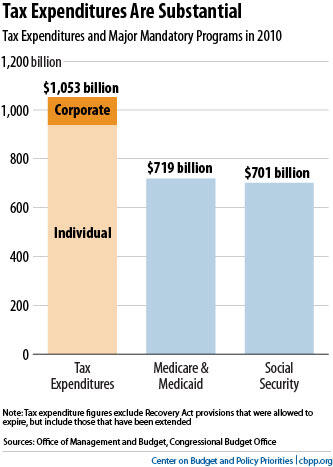

. . . The costs of tax expenditures are large. In 2010, individual tax expenditures totaled nearly $1 trillion, and total tax expenditures — both individual and corporate — amounted to $1.05 trillion. This greatly exceeded the cost of Medicare and Medicaid combined ($719 billion), Social Security ($701 billion), and non-security discretionary programs, which stood at $589 billion, a little over half of the cost of tax expenditures. [See graph.] . . .

[T]ax expenditures are not only costly, but often also economically inefficient. Although some tax expenditures are intended to adjust the amount of taxable income so as to better measure economic income or to reflect differences in ability to pay taxes, most tax expenditures are designed for another purpose — to subsidize certain desired activities — and often do so in inefficient ways that can detract from economic growth.Image

In cases where certain economic actions are believed to generate benefits shared by society at large, there may be strong arguments for designing the tax code to actively encourage these activities. But there are numerous ways to incentivize various desired activities, and the efficiency of any given tax incentive is heavily affected by how it is designed. Existing tax expenditures vary greatly in their effects on economic efficiency; some reduce economic efficiency by distorting investment or other economic decisions. . . .

Adding to their inefficiency, many tax expenditure provisions — principally deductions, exemptions, and exclusions — tie the tax subsidies they provide to the marginal tax rate of the beneficiary. The amount of the tax benefit provided increases with income, with the wealthiest households receiving the largest tax subsidies.

From an economic perspective, such a structure makes sense only if higher-income people need a substantially greater monetary incentive to take the desired action and wouldn’t take it without the tax incentive. Yet, as a number of tax experts and economists from across the political spectrum have explained, the reality is frequently the reverse; high-income families generally would send their children to college, make sure they have assets for retirement, and buy a home with or without the current costly tax incentives. Financially constrained families, by contrast, often would fail to engage in the socially desired activity without significant financial incentives.

That is why a number of liberal, conservative, and centrist experts alike have characterized key parts of our tax incentive structure as being “upside down” — we spend money providing the largest tax incentives to people in the top income tax brackets despite the fact that tax incentives generally have a much smaller effect on whether those individuals will send their children to college, become homebuyers, and put income aside for retirement. As tax experts Lily Batchelder (an NYU tax expert who now serves as chief tax counsel for the Senate Finance Committee), Fred Goldberg (who served as Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Tax Policy and IRS Commissioner under President George H. W. Bush) and former OMB director Peter Orszag wrote in 2006, “[P]roviding a larger incentive to higher-income households is economically inefficient unless policymakers have specific knowledge that such households are more responsive to the incentive or that their engaging in the behavior generates larger social benefits. . . .

[A]s long as we continue to use the tax code as a vehicle for advancing social policy, we should take steps to ensure that the tax incentives provided through the code are efficient, effective, and fair. And if we are going to step up to the plate and pursue deficit reduction, all parts of the budget — including the tax code — should be on the table and should contribute.

Click here for the full testimony.