BEYOND THE NUMBERS

State pension funding is back in the news today with a new update on state pension shortfalls from the Pew Center on the States. For the most part, the report — which is based on each state pension fund’s most recent Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) — gives a snapshot of pension funds two years ago, when they were still reeling from the effects of the 2008 stock market crash. The Pew report doesn’t account for the stock market’s improvement over the past two years, or the recent pension reforms in many states.

State pensions are underfunded — in some states, seriously so. As we’ve explained, however, restoring pensions to full health is a long-term goal that states should address with moderate measures, not an immediate crisis that requires drastic action.

For most states, the Pew report uses the pension fund’s CAFR for fiscal year 2009, which shows the fund’s assets and liabilities as of the end of the fiscal year (June 30, 2009 for most states). Not surprisingly, the report shows a significant decline in their condition compared to Pew’s previous report, which focused on 2008.

But there have been changes since then, primarily for the better.

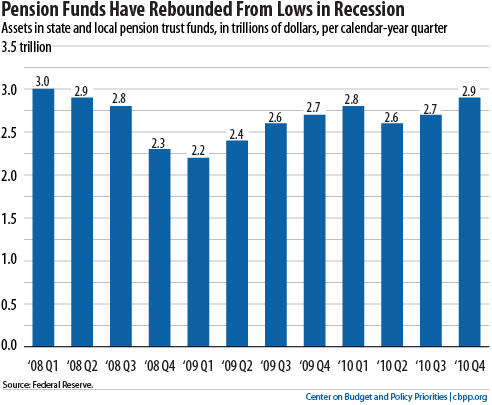

Federal Reserve data show that the rebounding stock market has lifted pension assets substantially over the past two years. The most recent data show assets at the end of 2010 were over $550 billion higher than in mid-2009 (see graph). The full impact of this increase won’t show up in state pension funds’ financial reports for several years, though. (To minimize year-to-year changes in the amount of money they must deposit in their pension funds, most states phase in the impact on fund assets of unexpectedly large investment gains and losses over a few years, by averaging those returns when calculating the value of pension fund assets.)

Also, states have taken numerous steps since 2009 to improve their pension systems’ fiscal health. The National Conference of State Legislatures reports that more than 20 states made changes in 2010 alone: 12 states upped employee contributions, for example, and 16 states reduced benefits. More than 30 states are considering similar measures this year. But it will take time for these steps to have their full impact on pension trust funds.

It would be both difficult and unnecessary for states to fully close their pension shortfalls immediately, as state economies and budgets continue to struggle with shrunken revenues and rising needs. Instead, states that haven’t already done so should act now to make a few relatively straightforward legislative changes that will help remedy under-funding over time, such as moderate increases in contributions by employees and the state and sensible changes to eligibility and benefit rules (such as measures to prevent uncommon but damaging abuses such as “spiking,” where employees artificially inflate their final year’s earnings in order to boost their pensions). We’ll outline these changes in an upcoming report.

The best estimate is that if states and localities over the next five years boost their pension contributions to roughly 5 percent of their budgets, on average (compared with today’s 3.8 percent), most states can restore their plans to full health over time, though the few states with particularly large pension shortfalls will likely need to impose larger changes. States that also reduce benefits or increase employee contributions could get by with a smaller increase in the state contribution.

In this way, states can avoid undermining either their employees’ retirement security or their ability to fund education, health care, infrastructure, and other public services necessary to the state’s long-term prosperity.