BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The House Energy and Commerce Committee will hold a hearing tomorrow on expiring provisions in federal health programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Four of them play critical roles in providing health coverage to families leaving welfare for work, helping low-income seniors and people with disabilities with their Medicare premiums, and enrolling more eligible low-income children in Medicaid and CHIP, as this updated paper explains.

Policymakers should extend these provisions in legislation that Congress is expected to move early this year to delay scheduled cuts in Medicare payments to doctors. If the legislation averts those payment cuts permanently (as bills passed by the Senate Finance Committee and the House Energy and Commerce and Ways and Means committees would do), Congress should make the four expiring Medicaid and CHIP provisions permanent as well.

The four provisions are:

Transitional Medical Assistance (TMA): TMA enables some low-income families that would otherwise lose Medicaid because their earnings have risen (or because they are receiving more child support) to get up to 12 months of temporary Medicaid coverage.

TMA, which expires on March 31, has become a critical source of health coverage for many low-income working families. It’s particularly important to parents in states that aren’t expanding Medicaid and have the opportunity to work their way off welfare; they could lose their Medicaid by taking a low-wage job that lifts their income over their state’s Medicaid income threshold, without gaining affordable coverage through their employer.

Qualifying Individuals Program (QI): Under QI, which also expires on March 31, states receive federal funding to defray Medicare Part B premiums for beneficiaries with incomes between 120 percent and 135 percent of the poverty line. About 520,000 near-poor elderly and disabled people received this assistance in fiscal year 2011. Without an extension, low-income seniors and people with disabilities will lose QI benefits that cover the full cost of their Part B premiums, which totaled $1,259 in 2013.

CHIPRA Performance Bonuses: Under the 2009 Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA), states can receive annual “performance bonuses” if they not only implement strategies that make it easier to enroll eligible low-income children in Medicaid and CHIP but also reach state-specific targets for boosting Medicaid enrollment among eligible children. The bonuses offset some state costs of enrolling more eligible children.

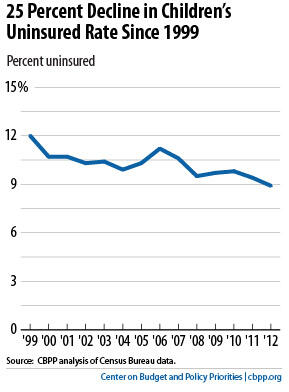

For fiscal year 2013, 23 states received a total of about $307 million in bonuses. The simplifications that states instituted have helped improve coverage among children; in 2012 — a year in which nearly half of states instituted one or more simplification — the share of children without health coverage reached a historic low of 8.9 percent, according to Census data, marking a 25 percent reduction since 1999 (see chart).

The CHIPRA performance bonuses expired at the end of September. Continuing them would help maintain progress in shrinking the number of uninsured low-income children.

Express Lane Eligibility (ELE): Under ELE, states can use information they have already collected to verify people’s eligibility for low-income programs such as SNAP (formerly food stamps) to streamline enrollment of eligible children in Medicaid and CHIP, rather than collecting and evaluating the same information all over again.

As of July 2013, 12 states (and the Virgin Islands) had taken the ELE option for Medicaid, CHIP, or both. ELE has already boosted the enrollment of eligible children and saved states time, which reduced administrative costs, according to a recent Government Accountability Office audit and a federal evaluation by Mathematica Policy Research.

While ELE doesn’t expire until the end of fiscal year 2014, extending it now would assure states that it will remain in place and thereby encourage more states to take it. That’s why the December 2012 “fiscal cliff” budget agreement included an early extension of ELE (which wasn’t scheduled to expire until the end of fiscal year 2013) through 2014.

Click here for the full paper.