BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Controversy has arisen over the amount of deficit reduction in President Obama’s fiscal year 2013 budget. Politifact last week questioned the validity of a CBPP analysis estimating that the Obama budget would reduce deficits by $3.8 trillion over ten years; Politifact suggested that the actual figure is below $3 trillion. Careful fact-checking shows, however, that our number is sound. The Politifact article went astray in several respects.

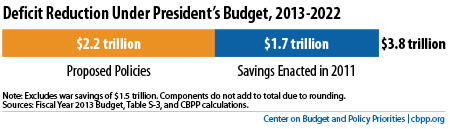

Our $3.8 trillion figure has two components (see graph):

- $2.2 trillion in savings from policies proposed in the President’s budget. (This figure does not include any savings from winding down the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, for which we did not give the budget credit.)

- $1.7 trillion in savings from discretionary spending cuts that policymakers enacted last year, primarily from the Budget Control Act’s caps on discretionary spending. Those savings, which will occur over the 2013-2022 period, implement the lion’s share of the discretionary cuts that the report from presidential deficit commission co-chairs Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson called for. (The $1.7 trillion figure includes the interest savings on the national debt that these discretionary cuts will produce.)

We issued the $3.8 trillion estimate in February 2012, based on estimates of the President’s budget from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates weren’t yet available. Now, they are. Under the CBO estimates of the President’s budget, the proposal would reduce the deficit by a slightly larger amount — about $4 trillion — over 2013-2022.

Current-Law Baseline Is Not Realistic

Politifact noted that compared to current law— that is, compared to a baseline that assumes policymakers will allow all tax and spending changes scheduled under current law to take effect — the Obama budget would actually increase the deficit. That is true. But virtually no budget observers think that policymakers will allow those changes to take effect; doing so would entail allowing all of the Bush tax cuts to expire, the Alternative Minimum Tax to explode and raise taxes for over 40 million Americans, physician payment rates in Medicare to be cut over 30 percent, and the like.

No recent deficit-reduction panel has measured its deficit savings compared to current law because such an assumption is almost universally rejected as highly unrealistic. Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson didn’t measure their deficit reduction from current law. Nor did the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Debt Reduction Task Force, chaired by former Senate Budget Committee Chairman Pete Domenici and former OMB and CBO director Alice Rivlin. Nor did the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (the supercommittee). Similarly, House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan measured the deficit reduction in the House budget plan he designed by comparing it to current policy rather than current law.

Politifact acknowledges this, saying that some independent groups doubt that a current-law baseline is realistic. It then says that if one measures deficit reduction compared to a continuation of current policy rather than current law, the Obama budget reduces deficits by close to $3 trillion — but not the nearly $4 trillion in the CBPP estimate. It cites the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) as its source.

Savings from Proposed Policies

According to Politifact, a CRFB analyst told it in a phone interview that the President’s budget saves $1.7 trillion relative to continuing current policy. The $1.7 trillion figure is lower, however, than CRFB’s own published estimates. In February, CRFB estimated that the savings in the Obama budget (not counting those already enacted) equaled $1.9 trillion for the 11-year period from 2012-2022, relative to current policy. (Analysts normally use a ten-year measuring period; CRFB’s 11-year period included some costs from stimulus that the Obama budget proposed for 2012.)

CRFB modified its estimates in March, putting the savings under the President’s budget for 2013-2022 at $2.3 trillion using OMB estimates and $2.4 trillion using CBO estimates. CRFB wrote, “Compared to more realistic current policy projections … the President’s budget would reduce deficits by $2.4 trillion.” This is actually a little higher than our $2.2 trillion estimate of the new savings under the Obama budget — and it’s substantially higher the $1.7 trillion figure Politifact used.

Savings Enacted in 2011

To this $1.7 trillion figure, Politifact added $1 trillion as the amount of deficit reduction that Congress passed in 2011. The figure appears to reflect the cuts in discretionary spending under the caps in last August’s Budget Control Act. But it misses several hundred billion dollars in additional discretionary cuts enacted earlier in 2011, and it may also overlook the related interest savings.

The actual savings from legislation enacted in 2011 are $1.7 trillion, using OMB estimates (and at least that amount using CBO estimates). When you add them to the new savings in the President’s budget — $2.2 trillion in our estimate and $2.4 trillion in CRFB’s analysis issued in March — the total is close to $4 trillion over 2013-2022.

It’s particularly important to include the savings enacted in 2011 because Bowles-Simpson and the Rivlin-Domenici task force issued their reports in late 2010. Since then, these two proposals have become benchmarks for assessing the size and composition of subsequent budget plans. To draw valid comparisons with the Bowles-Simpson and Rivlin-Domenici plans, it’s necessary to take account of legislation that policymakers enacted since they were issued — and that implement much of those plans’ proposals to limit discretionary spending.

At the time Bowles-Simpson and Rivlin-Domenici made their recommendations, the current-policy baseline assumed that discretionary spending would remain at the 2010 level, adjusted for inflation (and the phasing down of war costs). But, as noted above, Congress enacted legislation in 2011 that will reduce discretionary spending by at least $1.7 trillion over 2013-2022 (including the debt-service savings), compared to the 2010 baseline.

Ignoring the enacted savings would understate the total amount of deficit reduction that current budget proposals would achieve. It also would understate the overall share of deficit reduction achieved through program cuts rather than tax increases.

In short, a thorough examination supports our estimate that the President’s budget would, in combination with savings already enacted, reduce deficits by close to $4 trillion over ten years.