BEYOND THE NUMBERS

How Much More Deficit Reduction Do We Need Over the Coming Decade?

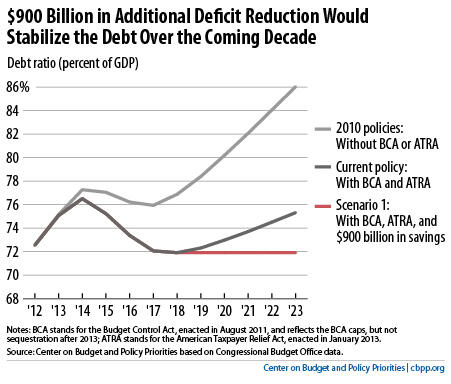

In February, CBPP estimated that $1.5 trillion in deficit savings would stabilize the debt (so it stops rising as a percent of the economy) over the latter part of the decade. But, the new, more optimistic budget projections the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released in May lowered deficits over that period by hundreds of billions of dollars. As a result, we now project that policymakers could stabilize the debt over the coming decade with about $900 billion in further deficit savings.

Our new analysis also notes that, while stabilizing the debt is the minimum goal, the improved fiscal outlook may make a more ambitious goal more attainable — one that includes temporary measures to strengthen job creation now while also taking sufficient steps to place the debt ratio on a downward path in the latter years of the decade.

As our analysis explains:

[C]urrent budget projections are considerably less daunting than they were a few years ago, as a result of CBO’s less pessimistic economic and technical assumptions and the spending and tax legislation that the President and Congress have enacted over the past 2½ years.

In this analysis, we also find that, in addition to the amount of deficit reduction to achieve over the coming decade, the timing of that deficit reduction is important. In particular, the amount of deficit reduction occurring during the latter part of the decade — and thus the resulting trajectory of the debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of the decade — is a key factor for assessing how various deficit-reduction policies will affect the outlook over the longer term, when the nation’s fiscal challenges will be greater.

If policymakers do not change current policies, the debt ratio will fall to 72 percent of GDP by 2018. After 2018, the debt ratio will start rising again because of the ongoing retirement of the baby-boom generation and the long-term pressure of health care cost growth (even after accounting for the recent slowdown). The debt ratio would exceed 75 percent of GDP by 2023 and continue rising gradually after that.

We estimate that $900 billion in deficit reduction that starts in 2019 could halt the rise of debt through the end of the decade, stabilizing the debt ratio at 72 percent of GDP. Stabilizing the debt ratio is the minimum appropriate fiscal policy during normal economic times because an ever-rising debt ratio is ultimately unsustainable. When times are good, the debt ratio should decline, to reduce the share of the budget devoted to interest on the debt and to allow for necessary debt increases during recessions, wars, and other crises.

Our analysis examines five scenarios of possible deficit-reduction amounts and paths that policymakers could follow. Based on those scenarios, we reach two sets of conclusions:

- Our estimate that $900 billion in deficit reduction could stabilize the debt ratio in the decade’s final years assumes sequestration does not continue beyond 2013. If, instead, policymakers maintain it, it will generate another $1.1 trillion in savings, producing a debt ratio of 71 percent in 2023. Yet, the debt ratio will still start rising at the end of the decade, partly because sequestration savings fade over time.

As a result, it would be far better — for budget policy, for the economy, and for the long-term debt trajectory — to replace sequestration with a balanced package of savings that phases in more slowly initially and more rapidly in the latter years of the decade. The debt trajectory during the latter part of the decade will generally be more important for the nation’s long-term fiscal health than the amount of deficit reduction over the next ten years.

- For any given amount of net 10-year deficit reduction, policymakers would be well-advised to include an up-front jobs package to help address the current high rates of unemployment and under-employment. By offsetting the cost of the jobs package over the decade, policymakers also could ensure that the gross 10-year deficit reduction would be greater and the debt ratio would have a better long-term trajectory.

For instance, while a $1.5 trillion ten-year deficit-reduction package would shrink the debt to 69 percent of GDP by 2023, the debt ratio would fall more rapidly in 2023 and produce better results in later decades if the package included $250 billion in temporary, up-front job-creation measures, offset by $250 billion in permanent revenue increases and program savings that continued to reduce the deficit beyond the next ten years.

With the debt ratio falling over the next few years under current policies, additional deficit reduction that is more back-loaded — and thereby targeted to reduce the deficit more in the final years of the decade, when the economy is expected to be stronger and when the debt ratio is projected to start rising again under current policies — would have a greater positive impact on the nation’s long-term fiscal outlook.