BEYOND THE NUMBERS

With a House subcommittee holding a hearing tomorrow on the future of Disability Insurance (DI), policymakers need to understand that DI is an essential part of Social Security.

Social Security is much more than a retirement program. It pays modest but guaranteed benefits when someone with a steady work history dies, retires, or becomes severely disabled. Although nobody likes to think that serious sickness or injury might knock them out of the workforce, a young person starting a career today has a one-third chance of dying or qualifying for DI before reaching Social Security’s full retirement age.

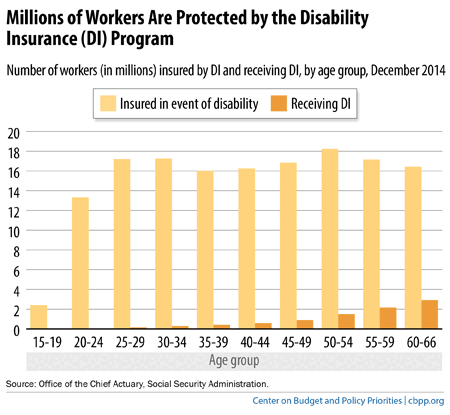

More than 150 million workers have earned DI protection through their payroll tax contributions in case they suffer a severe, long-lasting medical impairment. Nearly 9 million of them, mostly in their 50s and 60s, receive disabled-worker benefits from DI. (See chart.)

DI’s eligibility criteria are strict (applicants must provide convincing medical evidence from qualified sources, and most applications are denied) and its benefits modest (the average disabled worker receives $1,165 a month, and 99.4 percent get less than $2,500). DI is essential to recipients and their families, including nearly 2 million dependent children; because its benefits replace, on average, only about half of their lost earnings, DI beneficiaries are far likelier to be poor or near-poor than other Americans.

Social Security’s disability and retirement programs are closely integrated. Key features are similar or identical for the two programs, including the tax base, the work history required to become insured for benefits, the benefit formula, and cost-of-living adjustments. And at age 66, DI beneficiaries are seamlessly switched to retirement benefits without filing a fresh application. (That conversion used to occur at age 65, and the one-year delay is one of the demographic reasons behind DI’s growth.)

Despite those close links, the disability program’s trust fund is separate from the retirement and survivor program. There’s no longer any good reason for that — the 1979 Advisory Council recommended a merger of the trust funds — but lawmakers instead have relied on periodic reallocations of tax revenue between the two programs to shore up whichever trust fund needed it. They need to do so again to prevent a sudden, 20-percent cut in payments to vulnerable DI beneficiaries in 2016.

The need to replenish DI isn’t a crisis, nor would reallocating simply “kick the can down the road” as some contend. Instead it’d allow lawmakers to focus on the real task: assembling a package of revenue increases and modest benefit reforms to preserve long-term solvency for all of Social Security. Americans of all ages and incomes support Social Security and are willing to pay for it.