BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Social Security’s disability-insurance program is forecast to run short of money in 2018, more than six years from now, and policymakers can plug the hole for several decades by reallocating some taxes from the related old-age program as they have done in the past. But that’s not the impression you’d get from some alarmist reports. “Social Security disability on verge of insolvency” blares a Fox News story, a theme echoed by other outlets (see here and here).

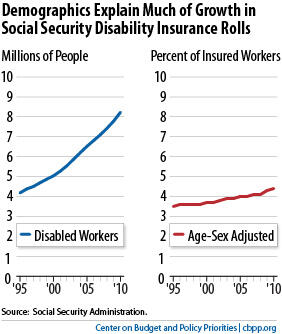

Here are the facts. In December 2010, 8.2 million people received disabled-worker benefits from Social Security. (Payments also went to some of their family members: 160,000 spouses and 1.8 million children.) Demographic and economic factors have pushed more people onto the disability rolls in recent decades; the number of disabled workers has doubled since 1995, while the working-age population — conventionally described as people age 20 through 64 — has increased by only about one-fifth. But that comparison is deceptive. Over that period:

- Baby boomers aged into their high-disability years. People are roughly twice as likely to be disabled at age 50 as at age 40, and twice as likely to be disabled at age 60 as at age 50. As the baby boomers (people born in 1946 through 1964) have grown inexorably older, disability cases have risen.

- More women qualified for disability benefits. In general, workers with severe impairments can get disability benefits only if they’ve worked for at least one-fourth of their adult life and for five of the last ten years. Until the great influx of women into the workforce in the 1970s and 1980s, relatively few women met those tests; as recently as 1990, male disabled workers outnumbered women by nearly a 2 to 1 ratio. Now that more women have worked long enough to qualify for disability benefits, the ratio has fallen to just 1.1 to 1.

- Social Security’s full retirement age rose from 65 to 66. When disabled workers reach the full retirement age, they begin receiving Social Security retirement benefits rather than disability benefits. The increase in the retirement age from 65 to 66 has delayed that conversion. Over 300,000 people between 65 and 66 now collect disability benefits; under the rules in place a decade ago, they’d be receiving retirement benefits instead.

While legally separate, Social Security’s Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and Disability Insurance (DI) trust funds are both funded by a payroll tax on the first $106,800 of earnings (a ceiling that’s updated annually). The DI trust fund is expected to run dry in 2018, but the two funds combined could pay full benefits until 2036. Congress has often reallocated payroll-tax revenue in the past — in either direction — to shore up the OASI or DI trust fund.

Disability benefits are an integral part of Social Security, closely woven into its package of retirement and survivor protections. Policymakers should act soon to restore solvency to all of Social Security and make any necessary tax-rate reallocations between the two trust funds at that time.